Tina Kim Gallery

525 West 21st Street

New York, NY 10011

212 716 1100

New York, NY 10011

212 716 1100

Founded in New York in 2001 by Tina Kim and located in Chelsea, Tina Kim Gallery is celebrated for its unique programming that emphasizes international contemporary artists, historical overviews, and independently curated shows. With the gallery’s strong focus on Asian contemporary artists, Tina Kim has created a platform for important emerging and renowned women artists such as Minouk Lim, Wook-Kyung Choi, and Suki Seokyeong Kang, and has become a go-to destination for Korean contemporary and historical art. Through its programming, the gallery works closely with internationally renowned curators for special exhibitions and produces scholarly art publications.

Artists Represented:

Chung Seoyoung

Davide Balliano

Ghada Amer

Gimhongsok

Ha Chong-Hyun

Kibong Rhee

Kim Tschang-Yeul

Kim Yong-Ik

Kwon Young-Woo

Lee Seung Jio

Lee Shinja

Minouk Lim

Mire Lee

Park Chan-kyong

Park Seo-Bo

Suh Seung-Won

Suki Seokyeong Kang

Tania Pérez Córdova

Wook-Kyung Choi

Pacita Abad

Works Available By:

Lee Ufan

Louise Bourgeois

John Pai

Minoru Niizuma

Chung Sang-Hwa

Chung Chang-Sup

Jennifer Tee

Ha Chong-Hyun

50 Years of Conjunction

November 7, 2024 - December 21, 2024

Tina Kim Gallery is pleased to announce Ha Chong-Hyun: 50 Years of Conjunction, a solo exhibition presented on the 50th anniversary of the artist’s widely celebrated Conjunction series. On view from November 7 - December 21, 2024, the exhibition will highlight major works from this signature series as it developed from 1974 to the present and will celebrate the artist’s enduring exploration of painting’s material possibilities.

Beginning with the first works made half a century ago, the essential act of the Conjunction paintings is the pushing through of oil paint from the back to the front of the artwork, so that the weave and texture of the burlap fabric becomes inextricably interwoven (or “conjoined”) with the oil. Ha’s use of burlap originated from resource constraints (burlap was an easily accessible fabric, used in army sandbags and American grain shipments after the Korean War) and from his explicit desire to work with “objects from the ruins of war”. Letting the properties of the material dictate his gestures, rather than the reverse, Ha made the first Conjunction paintings by stretching hemp over the four legs of an upturned table, and pushing paint through the loose weave of the fabric to bubble and drip over the roughly textured fibers on the other side.

Conjunction arose during a critical period of rapid industrialization and urbanization in Korea, following the end of 35 years of Japanese occupation, the Korean War, and the establishment of the Demilitarized Zone between North and South Korea in 1953. Without the signing of a peace treaty and a formal end to the war, nascent optimism in the 1960s and 70s was dampened by an extended military regime that imposed strict censorship and harsh anti-communist governance. Without the freedom to protest aloud, Ha Chong-Hyun turned to abstraction as a form of silent demonstration, using the physical method of his practice and the laborious pushing of paint to express a deeply felt resistance that could not be stated explicitly. Other artists of his generation such as Park Seo-Bo, Lee Ufan, and Kwon Young-Woo expressed a similar interest in materiality and restraint, eventually coming to be known as the Dansaekhwa movement, now seen as one of the pillars of Korean modernism.

Ha’s interest in the monochrome rejected minimalism’s penchant for the smooth and seamless, always leaving evidence of his mark making across the surface. Conjunction also marked a clear departure from his early Informel period, as well as White Paper for Urban Planning, a series of brightly colored geometric abstractions that were in dialogue with an international interest in the vocabulary of line and form. The Conjunction paintings rejected the central premise and tools of painting entirely, using rudimentary hand-made tools to push and scrape his paint through the fabric, rather than daub and spread onto the surface. Early works from the series drew from the colors of everyday life in Korea, including hues from paper, ceramics, earth, traditional roof tiles, and hemp. His contemporary Conjunction works are highly gestural, vivid, and expressive, evolving the artist’s continued devotion to experimentation and inquiry in painting.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Ha Chong-Hyun has lived and worked in Seoul since graduating from Hongik University in 1959, where he served as the Dean of the Fine Arts College from 1990 to 1994. From 2001 to 2006, Ha was the Director of the Seoul Museum of Art. Ha has exhibited in major institutional presentations around the world, including at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, Art Institute of Chicago, Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Gwacheon, the Denver Art Museum, Song Art Museum in Beijing, the Brooklyn Museum in New York, Erarta Museum in St. Petersburg, Fondazione Mudima in Milan, as well as the Venice Biennale, Paris Biennale, São Paulo Biennale, Gwangju Biennale, and Busan Biennale, among others. His works are included in the permanent collection of various renowned institutions, such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York; Art Institute of Chicago; M+ Museum in Hong Kong; National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) in Korea; Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum; the Museum of Contemporary Art in Hiroshima; and the Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art in Seoul.

ABOUT THE GALLERY

Tina Kim Gallery is widely recognized for its unique programming that emphasizes

international contemporary artists, historical overviews, and independent curatorial projects.

The gallery has built a platform for emerging and established artists by working closely with over twenty artists and estates, including Pacita Abad, Ghada Amer, Tania Pérez Córdova, and Mire Lee, amongst others. Our expanding program of Asian-American and Asian diasporic artists, including Maia Ruth Lee, Minoru Niizuma, and Wook-Kyung Choi, evince the gallery’s commitment to pushing the conversation beyond national frameworks.

Founded in 2001, the gallery opened the doors to its ground-floor Chelsea exhibition space in 2014. The gallery was instrumental in introducing Korean Dansaekhwa artists such as Park Seo-Bo, Ha Chong-Hyun, and Kim Tschang-Yeul to an international audience, establishing public and institutional awareness of this critically influential group of Asian Post-War artists. The gallery partners regularly with prominent curators, scholars, and writers to produce exhibitions and publications of rigor and critical resonance.

Kibong Rhee

There is no place

October 3, 2024 - November 2, 2024

Tina Kim Gallery is pleased to announce “There is no place,” a solo exhibition of new works by Kibong Rhee on view from October 3rd to November 2nd. It marks the artist’s second solo show at the gallery following his New York debut in 2011. An opening reception with the artist present will take place on Thursday, October 3rd from 6–8pm.

Since the 1980s, Rhee has consistently explored in his practice the interconnectedness of the world, specifically cycles of creation, dissolution, and regeneration, as well as the dynamic interplay between matter and spirit. Probing the meanings that emerge within these structures, he captures the coexistence of multiple realms and makes abstract concepts tangible. His works visually combine natural phenomena such as light, wind, water, and foam with the mechanical to evoke sensorial contemplation of the immaterial world that lies beyond perception. The relationships between disappearance and impermanence, and presence and absence are particularly central to his long-standing practice.

Although Rhee worked primarily with sculpture and installation prior to the 2000s, he has become deeply engrossed in the potential of painting as a “device” and the concept of “painting as passage.”[1] Layering transparent fabric over his canvases, Rhee paints his primary motif—trees bathed in mist—with an almost photographic precision. Water plays a crucial role in his oeuvre, as Rhee believes that water, in its variety of forms, embodies the fleetingness of life. As Rhee states, “The world is inherently either blurry or chaotic;” and mist, in his paintings, both conceals objects and provokes viewers to approach the work.[2] His fog- shrouded landscapes evoke an air of mystery, a world where reality and illusion intermingle. His vignettes appear suspended in an in-between state, either materializing or disappearing. Rhee’s paintings do not aim for perfect representation; rather, they question the very possibility of it. The artist seeks to convey the incomplete nature of the world, opening up a philosophical space to explore what cannot be fully articulated.

Rhee’s landscapes are filled with a sense of stillness; time seems to weigh on the motionless branches as the silent passage of time continues to flow. In a monumental, 10-meter-long landscape from Rhee’s Mistygraphy series, viewers can immerse themselves in this experience of time. The titles of two other works, The Left Page and Recto and Verso (both 2024), aptly capture a liminal sense of temporality. The unopened left page (verso) of a book and the right page (recto), soon to be part of the past, suggest a space where the future carries traces of what came before.

Differences – Remnant and Differences – Absence (both 2024) resemble the appearance of an after-image, and visually attest to the notion that life is an ongoing attempt to revisit and reconcile unresolved remnants of the past. It is the continuous tension between the ever-renewing present and the anticipation of an unknowable future. Much like the way film passes through a movie projector interspersed with alternating frames of darkness, the world is suspended in the brief blackout between the opening and closing of eyelids. With each blink, the world disappears and is reborn.

Also featured in “There is no place” is the installation Mistygraphy – Cut Section (Last) (2024), which revisits the 2016 piece Perpetual Snow. Here, a transparent glass screen foregrounds a black wall, reflecting the viewer’s image within the exhibition space. In the original 2016 work, a kinetic sculpture modeled after the artist’s hand continuously creates small circular patterns across a glass surface, symbolizing eternal snow. In its latest form, the work reflects the fleeting presence of passing visitors. Viewers find themselves becoming part of the work, experiencing both presence and absence in that fleeting moment. Through this psychological and sensorial interaction, Mistygraphy – Cut Section (Last) invites contemplation on the nature of existence and transience.

Through his work, Rhee does not merely ask what is present, but persistently questions what is disappearing. The ephemeral beings in his mist-soaked worlds invite us to consider what can truly be represented, what lies at the boundaries of perception, what those boundaries might reveal, and what moments are only possible within such limits.

[1] Jinsang Yoo, “Wet Psyche by Kibong Rhee: Art of Humidifying Surfaces,” in Kibong Rhee: The Wet Psyche (Seoul: Kukje Gallery, 2008), 16–22

[2] Eun-joo Lee, “Blurry or Chaotic, the World is One or the Other,” JoongAng Ilbo, December 12, 2022.

Lee Shinja

Lee Shinja: Weaving the Dawn

August 22, 2024 - September 28, 2024

Tina Kim Gallery is pleased to announce “Weaving the Dawn,” the gallery’s first solo exhibition dedicated to Lee ShinJa—a pioneering artist who is remembered in Korean art history for introducing the “tapestry” genre when the concept of “fiber art” was still unestablished in her native Korea. Marking her New York debut, the show will highlight Lee’s expansion of the material characteristics and aesthetic beauty of thread as a medium. The full breadth of her career, which spans more than half a century, will be represented—from her avant-garde embroidered appliqué work from the 1960s to the more recent “Spirit of Mountain” series that pays homage to her hometown. Featuring preliminary sketches of her early compositional ideas and archival materials that highlight her role as a dedicated educator and researcher, “Weaving the Dawn” will be on view from August 22 to September 28, 2024, with a reception taking place on Friday, September 13, from 6–8 pm.

Pacita Abad

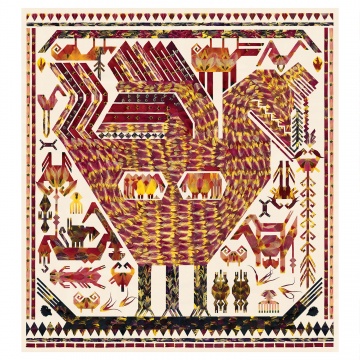

Pacita Abad: Underwater Wilderness

June 27, 2024 - August 16, 2024

“I always see the world through color, although my vision, perspective, and paintings are constantly influenced by new ideas and changing environments.”

— Pacita Abad (1946–2004)

Tina Kim Gallery is pleased to present “Underwater Wilderness,” the gallery’s second solo show dedicated to the late Filipina-American artist Pacita Abad. Featuring eight monumental trapuntos, a form of textile-painting that Pacita pioneered, this exhibition offers a focused selection of significant work created between 1985 and 1989 from a small series inspired by the artist’s fantastical experiences scuba diving in the Philippines. The whimsical paintings originally debuted as an immersive installation in 1986 at the Ayala Museum in Manila, andwill be reunited in New York for thefirst time since their 1987 display at the Philippine Center.On view at the gallery from June 27th to August 16th, this stirring presentation runsconcurrently with Pacita’s major retrospective at MoMA PS1, which closes on September 2nd before traveling to the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

The “Underwater Wilderness” series developed afer Pacita learned to dive at the British Sub-Aquatic Club in Thailand in the 1980s. Prior to this, she had a fear of water afer a traumaticchildhood experience in which she nearly drowned. Conquering her aquaphobia, Pacita became a proficient scuba diver and made over 80 dives across the Philippines, from SepocBeach to Dumaguete, Puerto Galera, Apo Island, and the Hundred Islands. The wondrous sub-aquatic ecosystems that Pacita encountered during her dives provided ample inspiration forthe inveterate colorist.

These dense, kaleidoscopic, and sensorial paintings—marked by Pacita’s signature vibrancy and visible stitching—transport viewers to a mesmerizing undersea locale. To portray the inspiring and lush marine environments that left her in awe, Pacita sewed pieces of fabric together to form complex and layered compositions before painting and embellishing thecanvas. In Dumaguete’s Underwater Garden (1987), she clearly delineates parts of the reef through a laborious combination of stitching and stuffing while rendering other parts inimpressionistic strokes to create the illusion of motion. In Shallow Gardens of Apo Reef (1986), fluorescent corals, sinuous vegetation, and diverse aquatic life emerge through a highlyinventive use of found materials culminating in a maximalist, vertical composition.

An abiding interest in alternative, non-hegemonic systems of meaning connects Pacita’s diverse subject matter, from the politically charged “Immigrant Experience” works exploring the possibility of “third-world” solidarities to the idiosyncratic “Masks and Spirits” series tackling complex questions about the mutability of representation and tradition in modernity. Though described by critics as her least political body of work, “Underwater Wilderness” harkens back to the artist’s Ivatan roots and connection to Batanes, Philippines, where she was born and raised. The series can perhaps be read as Pacita’s bridging of personal and political histories and the “manifold lived realities” of the Philippines. Afer she led student demonstrations against dictator Ferdinand Marcos in the late ’60s, her parents encouraged her to complete her studies abroad afer her family home was sprayed with bullets. She was only able to return to live in the Philippines in 1982 afer twelve years away, and started this body of work the year before the fall of the kleptocratic regime in 1986.

For an artist whose multimodal life resists essentialization, “Underwater Wilderness” further complicates the discourse around her practice. When describing her diving experience, Pacita said that she felt like “an infidel intruding into somewhere sacred.” In a body of water where different currents both literal and metaphorical collide, Pacita found a space of liberation, recovery, and possibility.

In a body of water where different currents both literal and metaphorical collide, Pacita found a space of liberation, recovery, and possibility. When describing her diving experience, Pacita said that she felt like “an infidel intruding into somewhere sacred.” For an artist whose multimodal life resists essentialization, “Underwater Wilderness” further complicates the discourse around her practice.

Pacita Abad

Underwater Wilderness

June 27, 2024 - August 16, 2024

“I always see the world through color, although my vision, perspective, and paintings are constantly influenced by new ideas and changing environments.”

— Pacita Abad (1946–2004)

Tina Kim Gallery is pleased to present “Underwater Wilderness,” the gallery’s second solo show dedicated to the late Filipina-American artist Pacita Abad. Featuring eight monumental trapuntos, a form of textile-painting that Pacita pioneered, this exhibition offers a focused selection of significant work created between 1985 and 1989 from a small series inspired by the artist’s fantastical experiences scuba diving in the Philippines. The whimsical paintings originally debuted as an immersive installation in 1986 at the Ayala Museum in Manila, andwill be reunited in New York for thefirst time since their 1987 display at the Philippine Center.On view at the gallery from June 27th to August 16th, this stirring presentation runsconcurrently with Pacita’s major retrospective at MoMA PS1, which closes on September 2nd before traveling to the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

The “Underwater Wilderness” series developed afer Pacita learned to dive at the British Sub-Aquatic Club in Thailand in the 1980s. Prior to this, she had a fear of water afer a traumaticchildhood experience in which she nearly drowned. Conquering her aquaphobia, Pacita became a proficient scuba diver and made over 80 dives across the Philippines, from SepocBeach to Dumaguete, Puerto Galera, Apo Island, and the Hundred Islands. The wondrous sub-aquatic ecosystems that Pacita encountered during her dives provided ample inspiration forthe inveterate colorist.

These dense, kaleidoscopic, and sensorial paintings—marked by Pacita’s signature vibrancy and visible stitching—transport viewers to a mesmerizing undersea locale. To portray the inspiring and lush marine environments that left her in awe, Pacita sewed pieces of fabric together to form complex and layered compositions before painting and embellishing thecanvas. In Dumaguete’s Underwater Garden (1987), she clearly delineates parts of the reef through a laborious combination of stitching and stuffing while rendering other parts inimpressionistic strokes to create the illusion of motion. In Shallow Gardens of Apo Reef (1986), fluorescent corals, sinuous vegetation, and diverse aquatic life emerge through a highlyinventive use of found materials culminating in a maximalist, vertical composition.

An abiding interest in alternative, non-hegemonic systems of meaning connects Pacita’s diverse subject matter, from the politically charged “Immigrant Experience” works exploring the possibility of “third-world” solidarities to the idiosyncratic “Masks and Spirits” series tackling complex questions about the mutability of representation and tradition in modernity. Though described by critics as her least political body of work, “Underwater Wilderness” harkens back to the artist’s Ivatan roots and connection to Batanes, Philippines, where she was born and raised. The series can perhaps be read as Pacita’s bridging of personal and political histories and the “manifold lived realities” of the Philippines. Afer she led student demonstrations against dictator Ferdinand Marcos in the late ’60s, her parents encouraged her to complete her studies abroad afer her family home was sprayed with bullets. She was only able to return to live in the Philippines in 1982 afer twelve years away, and started this body of work the year before the fall of the kleptocratic regime in 1986.

For an artist whose multimodal life resists essentialization, “Underwater Wilderness” further complicates the discourse around her practice. When describing her diving experience, Pacita said that she felt like “an infidel intruding into somewhere sacred.” In a body of water where different currents both literal and metaphorical collide, Pacita found a space of liberation, recovery, and possibility.

In a body of water where different currents both literal and metaphorical collide, Pacita found a space of liberation, recovery, and possibility. When describing her diving experience, Pacita said that she felt like “an infidel intruding into somewhere sacred.” For an artist whose multimodal life resists essentialization, “Underwater Wilderness” further complicates the discourse around her practice.

Suki Seokyeong Kang

May 2, 2024 - June 15, 2024

Tradition is about thinking about the present more deeply.*

—Suki Seokyeong Kang

Tina Kim Gallery is pleased to announce Suki Seokyeong Kang, the gallery’s second solo exhibition of leading South Korean contemporary artist Suki Seokyeong Kang, opening May 2 and running through June 15, 2024. Expanding on the themes that characterize Kang’s critically acclaimed multimedia practice, the exhibition will include works never before seen in New York, many of which were specifically created for her major 2023 solo exhibition, Willow Drum Oriole, held at the Leeum Museum of Art, in Seoul.

The theme of being present connects the diverse works in this exhibition. Kang’s practice centers on the exploration of tension, boundaries, and balance. Her paintings and sculptures negotiate a harmony between old and new, reinterpreting traditional art forms like Jeongganbo and Chunaengmu in contemporary contexts.1 References to the four seasons, works evoking sound and movement, and the balancing of near and far views create a sense of wholeness and inevitability, asking viewers to find peace and presence in the here and now.

On view in the gallery are works from Kang’s celebrated series Jeong, Mat, Narrow Meadow, and Mora, as well as two new sculpture series, Mountain and Column. For each of these bodies of work, she has developed a distinct formal vocabulary that combines traditional techniques with specific materials to create dynamic forms inspired by Korean culture yet deeply engaged with contemporary social issues and art history. Rooted in her training as a traditional painter, Kang’s works explore how, despite our many differences, we remain connected. In focusing on how ideas of the past manifest today, Kang employs the traditional concept of “Jinkyung,” or “true-view,” painting, which seeks to represent the essence of the subject through the principle of shared symbolism. In this way, her work frames what she describes as “the beautiful moment of sharing time,” assisting us in being present in a space where “we can constantly reconcile imbalances and conflicts and achieve complete harmony with each other.”

* Quoted in Connie Butler, “The Subtle Smile: Suki Seokyeong Kang’s Sympathetic Object,” in Willow Drum Oriole (Seoul: Leeum Museum of Art, 2023). All quotes by the artist are from this exhibition catalogue.

1 Jeongganbo is a type of musical notation dating back to the Joseon dynasty, in which the duration and pitch of sounds are notated within a square grid shaped like the character “Jeong” (井). Chunaengmu, or the Dance of the Spring Oriole, is a solo Korean court dance that originated during the later period of the Joseon dynasty.

Chung Seoyoung

With no Head nor Tail

March 21, 2024 - April 20, 2024

Tina Kim Gallery is pleased to announce Chung Seoyoung (b. Seoul, 1964)’s With no Head nor Tail, from March 21 to April 21, 2024. This marks the artist’s second solo exhibition with the gallery since 2017. In a 1996 interview, shortly after Chung’s artistic career began, she described her work as the “reciprocal motion between the unreal and real, the abstract and concrete.”[1] This description, which diverges from our conventional understanding of sculpture, suggests that sculpture for Chung is an articulation of the negative spaces in between the beliefs and notions that we have come to recognize and categorize. With no Head nor Tail presents works from a transitional phase in Chung’s practice, re-examining the medium of sculpture from “all possible conditions of reference,”[2] including objects, time, space, text, sound, and the viewer’s body in motion.

Many of Chung’s motifs often depict moments where abstract concepts intersect with ephemeral forms, such as ghosts, waves, and fires. The title of this exhibition seeks to evoke with a touch of humor the essence of a ghost – its shape constantly shifting, unable to be pinned down through language. Included in With no Head nor Tail will be early works from the 1990s where Chung has utilized everyday objects, to drawings that bridge the blindspots in perception through language and imagery. Furthermore, works that are composed of and keenly bring out the subtle innate qualities of materials that elicit memories of a certain socio-economical moment in Korea and references such as flooring decals, plastic, plywood, artificial plants, furniture, retro typefaces, bronze, and ceramics, culminate in what Chung denotes as “sculptural moments.”

Road (1993) and Sink (2011) are representative of works that Chung has composed with ordinary, commonplace objects. Originally exhibited at the abandoned substation in Singen, Germany, as part of the group exhibition Symposion Umspannwerk in 1993, Road consists of plastic buckets placed on wheeled legs, containing wooden balls with intersecting roads drawn on them. As suggested by the wheels and the round wooden balls, Road becomes a form representing continuous space and time, while the bucket serves as a container for these elements in motion. Another work that contains an everyday item is Sink (2011), which debuted at Apple vs. Banana, the artist’s solo exhibition held in a defunct model house in Seoul in 2011. Sink encourages a re-evaluation of familiar consumer goods and an examination of their already “known” appearances as if they were a blank canvas. For Chung, objects do not merely serve the function of creating sculpture. But rather, she seeks to bring out what has yet to be said about them – opening up other passageways that differ from and go beyond accepted and superficial points of view.

This exhibition presents an opportunity to engage with recent works that reveal the artist’s long-standing investigation of the relationship between language and perception. Deep Sea and Thick Wall (2024) is a standing sculpture composed of white panels silkscreened with text that reads: “staring into the deep sea and a thick wall is the same? the.” The text itself is written in typography reminiscent of South Korean grade school art classes in the 70s and 80s – a time when students had to create posters as part of the state-mandated collective social education curriculum. It is not that Chung seeks to align a “deep sea” and a “thick wall” as being the same, but rather that through sharing in the “act of looking,” she is able to mediate and erase the perceived boundary between the two. Another series with a prominent use of language is the A4-sized ceramic drawings. Some of them feature simple drawings made with gold glaze, while others have Korean characters that Chung inscribed using glaze pencils while using a ruler. Residual traces of pigment smudged by the ruler appear on the white, matte surface of the porcelain, evoking transience and ephemerality. Therefore, the consonants, vowels, words, and phrases appear like remnants of form and sound. Echoing Chung’s maxim – “When the object is cumbersome due to scale, I let drawing do the work” – the materiality of language is in a sense, an abstract sculpture.

Some senses are stronger than that of sight. Chung’s most recent work Red (2024) began with the artist’s vivid memory of encountering writer Charlotte Brontë’s dress displayed at the Morgan Library in New York. To be conceived as having belonged to a living person, the dress seemed too peculiar in size, thereby the experience generated a new relationship between the subject of the dress and the artist's body. This strange encounter lingered within the artist, creating an intense urge “to make something from what I've seen and what I know, but at the same time, has no meaning.”

Let us now recall the title of Chung's most recent retrospective, What I Saw Today (Seoul Museum of Art, 2022), which at first may sound unremarkable and detached. But Chung's decision to use the word “today,” rather than “yesterday” or “back then,” is significant because her sculptures aim to go beyond merely describing or representing past experiences in the present.[3] Chung says, “For the past 4.5 billion years, the sun has visited us without fail, every single day of the year.”[4] By situating her work alongside the sunrise, Chung evokes the continual passing of time, while still calling to mind that each sunrise is a new and unique event, because there will always be only one “today.” Essential to Chung’s sculpture is this heterogenous understanding of temporality that allows for the experience of simultaneity through time’s cyclical nature, while acknowledging time’s linearity. Still pertinent in 2024, Chung’s works capture this fleeting convergence where the subjective and the objective come together in time and space.

[1] Lee Jong-soong, “Between What Can Be Said and What Cannot Be Said: Thoughts on the Recent Works of Chung Seoyoung,” Space, January 1996.

[2] Lee Hanbum, “Chung Seoyoung and about Chung Seoyoung,” manuscript presented at Language Activity, a public program in the occasion of exhibition Chung Seoyoung Solo Show (Audio Visual Pavilion, 2016).

[3] Jihan Jang, “Ghost, Object, Sculpture: The Sculptural Moment of Chung Seoyoung,” Chung Seoyoung: What I Saw Today (Milan: Skira, 2022).

[4] Excerpted from Chung Seoyoung, Continuity, 2020. Single-channel video installation, dimensions variable.

Back to all Member Galleries

Back to all Member Galleries