Paula Cooper Gallery

534 West 21st Street

New York, NY 10011

212 255 1105

Also at:

529 West 21st Street

New York, NY 10011

212 255 1105

521 West 21st Street

New York, NY 10011

212 255 1105

New York, NY 10011

212 255 1105

Also at:

529 West 21st Street

New York, NY 10011

212 255 1105

521 West 21st Street

New York, NY 10011

212 255 1105

Paula Cooper Gallery, the first art gallery in SoHo, opened in 1968 with an exhibition to benefit the Student Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam. The show included works by Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, Robert Mangold and Robert Ryman, among others, as well as Sol LeWitt’s first wall drawing. For fifty years, the gallery’s artistic agenda has remained focused on, though not limited to, conceptual and minimal art.

In 1996, the gallery moved to Chelsea to occupy an award-winning redesigned 19th century building. The architect was Richard Gluckman. In 1999, Paula Cooper opened a second exhibition space on 21st Street. In 2020, the Gallery was pleased to open a new, seasonal location in Palm Beach, Florida.

Beyond its immediate artistic program, the gallery has regularly hosted concerts, music symposia, dance performances, book receptions, poetry readings, as well as art exhibitions and special events to benefit various national and community organizations. For 25 years until 2000, the gallery presented a much celebrated series of New Year’s Eve readings of Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans and James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake.

Artists Represented:

Carl Andre

Estate of Terry Adkins

Tauba Auerbach

Estate of Jennifer Bartlett

Estate of Bernd and Hilla Becher

Céleste Boursier-Mougenot

Cecily Brown

Sophie Calle

Beatrice Caracciolo

Estate of Sarah Charlesworth

Estate of Bruce Conner

Estate of Jay DeFeo

Mark di Suvero

Sam Durant

Estate Luciano Fabro

Matias Faldbakken

Ja'Tovia Gary

Liz Glynn

Robert Grosvenor

Hans Haacke

Estate of Douglas Huebler

Ralph Lemon

Julian Lethbridge

Estate of Sol LeWitt

Eric N. Mack

Christian Marclay

Justin Matherly

Peter Moore

David Novros

Estate of Claes Oldenburg & Coosje van Bruggen

Paul Pfeiffer

Walid Raad

Veronica Ryan

Joel Shapiro

Rudolf Stingel

Kelley Walker

Dan Walsh

Meg Webster

Robert Wilson

Jackie Winsor

Bing Wright

Carey Young

Works Available By:

Lynda Benglis

Jane Benson

Jonathan Borofsky

Dan Flavin

Michael Hurson

Donald Judd

Sherrie Levine

Jan Schoonhoven

Alan Shields

Atsuko Tanaka

Exhibition view of Carl Andre, at Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, 2014. © Carl Andre / VAGA 2014. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

Atsuko Tanaka, Yayoi Kusama

May 8, 2025 - June 14, 2025

Atsuko Tanaka, Yayoi Kusama brings together the works of two of Japan’s most innovative and influential artists. Featuring a selection of works on canvas and paper spanning Tanaka’s career, and early works in various media by Kusama, this exhibition offers an opportunity to explore the parallel yet distinct artistic concerns of these pioneering figures in postwar abstract art. A fully illustrated catalogue is published to accompany the exhibition, featuring an essay by Anthony Allen.

Atsuko Tanaka (1932-2005) and Yayoi Kusama (b. 1929) both came of age in the aftermath of World War II, during a period of profound societal transformation in Japan that sparked radical shifts and innovations in the arts. Tanaka, a core member of the avant-garde Gutai movement from 1955 to 1965 and one of its few female artists, is best known for her vibrant works where circles and lines engage in dynamic interplay. Her Electric Dress (1956), a garment composed of incandescent bulbs and connecting wires, remains her most iconic work and encapsulates her fascination with notions of technological change, artificiality, and disjunction at the heart of modernity. Meanwhile, Kusama lived in New York from 1958 through 1973, and actively participated in the vibrant art scene of the 1960s. Her work of this period engaged with the hypnotic power of repetition, often evolving into immersive pieces that evoked hallucination, boundlessness and self-obliteration. Her art reflects a preoccupation with themes of obsession, depersonalization and liberation, hallmarks of an alienated age. Both artists shared a broadened approach to artmaking, incorporating textiles, fashion, sensory environments, performance, and participatory elements into their work. Each developed a deeply personal abstract language built around repeated motifs and a keen interest in large, enveloping scale.

The exhibition will present a diverse selection of works on paper and canvas by each artist. It will include examples of Tanaka’s early drawings inspired by her Electric Dress, paintings from the Gutai period and beyond, as well as a small group of watercolors made for Sam Francis. Also on view will be a selection of Kusama’s pioneering Infinity Nets paintings from the 1960s, alongside rare collages, photographs and early pastels. In addition to these works, the exhibition will include documentary photography by Peter Moore and Kiyoji Otsuji, capturing pivotal moments in the artists’ careers, and three films: Kusama’s Self-Obliteration by Jud Yalkut along with Round on Sand and Tanaka’s Round Circle by Tanaka.

Claes Oldenburg & Peter Moore

New York Streets & Signs

April 17, 2025 - June 14, 2025

Claes Oldenburg and Peter Moore both moved to New York in the mid–1950s and were immediately struck by the city’s streets, in particular the sidewalks, storefronts and signage that clamored for attention. Keenly alert to the visual assault of language and communication, Oldenburg made drawings and sculptures of storefronts, street objects and text-based posters, while Moore produced a historical record of city signage through documentary photographs. The exhibition will display key examples from these bodies of work, including pieces from Oldenburg’s legendary installations The Street (1960) and The Store (1961) that interpret the urban environment depicted in Moore’s images. Similarly attentive to witty juxtapositions of words and phrases as well as the cycle of urban transformation and capitalist expansion, Oldenburg and Moore confronted the overall theatricality of the city’s streets with equal parts mischief and grit.

Oldenburg described his obsession with the street and its stores in 1961: “The goods in the stores, the billboards, the signs, wrappers, etc., all these things attract me very much, and I find myself wanting to imitate them.”[1] His emulation had begun with The Street (1960), an installation and exhibition in two parts at the Judson Gallery and the Reuben Gallery. The layering of posters and bills, which the artist described as the “[superimposed] residue of hopeless dreams” was particularly appealing, and Oldenburg produced a series of monotypes in ink on newsprint paper to promote performances that took place inside The Street. [2] Some were wheat-pasted around the neighborhood in an effort to “harmonize” his exhibition with the urban reality, and several of the surviving examples will be installed in the exhibition.[3]

Oldenburg’s Store was modelled on local mom-and-pop stores that manufactured and sold their products in-house, and it is those bygone businesses that appear in Moore’s photographs, their displays squarely positioned within the frame to provide a direct window into the past. Known for his essential documentation of the avant-garde, performance art, and the demolition of the original Pennsylvania Station, Moore was also a senior editor of Modern Photography magazine. His keen editorial eye and enthusiasm for eccentricity drove him to seek out and document notable and striking signage of all kinds—“Arthur P. Slaughter”, purveyor of “Furs & Skins” and the “Lovable Brassiere Co.” responsible for “Purchasing & Research”. Like Oldenburg, Moore was drawn to alternate spellings and opportune errors that forced the reader to slow down and enunciate, such as “Specialtise…in Italian Cooking” and a charming hand-drawn pricelist of “Sandwishes” pasted inside a store window. Photographs of glowing cinemas and neon awnings capture New York’s sleazy glamour and reflect a city in constant flux—grimy, eerie and irresistible.

Claes Oldenburg and Peter Moore were part of the same close-knit downtown art scene that flourished in the 1960s and 1970s. Moore photographed Oldenburg on multiple occasions––both his public performance “Washes” (1965) in the swimming pool at Al Roon’s Health Club and portraits in Oldenburg’s studio and on the Lower East Side (1966).

[1] Claes Oldenburg: Writing on the Side 1956–1969 (The Museum of Modern Art, New York: 2013), p. 152

[2] Ibid, p. 23

[3] Claes Oldenburg in Richard H. Axsom and David Platzker, Printed Stuff: Prints, Posters, and Ephemera by Claes Oldenburg, exh. cat. (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1997), p. 12

Sarah Charlesworth

Sarah Charlesworth: Seduction and Desire

February 20, 2025 - April 12, 2025

Sarah Charlesworth (1947–2013) is known for her conceptually driven and visually alluring photo-based works that subvert and deconstruct cultural imagery. Entitled Desire and Seduction, the current exhibition will examine how these themes emerged and recurred within Charlesworth’s work from the early 1980s through the mid-2000s. Populated with fetish objects and silken fabrics, isolated body parts and masked strangers, the exhibition invites the viewer to locate their own desire.

Beginning with her celebrated Objects of Desire series (1983–88), Charlesworth sought to make visible the “shape of desire.”[1] Meticulously excising images from a range of sources—including fashion magazines, pornography, and archeological textbooks—she then re-photographed the cutouts against fields of pure color. In each work, Charlesworth has paired the image with a signifying color: red (sexual passion), black (dominance or death), green (natural growth), yellow (material value), blue (spiritual or metaphorical desire). The prints are enclosed within coordinated lacquered wood frames and either stand alone or are combined in diptychs and triptychs.

The earliest works in the exhibition address sexuality through gender stereotypes, such as the toned male torso outlined in clinging wet fabric in White T-Shirt (1983), a sweep of voluminous locks in Blonde (1983–84) and the anonymous wedding dress in Bride (1983–84). Charlesworth disrupts the viewer’s expectations in Red Mask (1983) with an image of an onnagata Kabuki actor playing the role of a geisha. In the two-part work Figures (1983), a silk evening gown is juxtaposed with a satin bondage suit on black and red backgrounds, intertwining dominance, power and passion.

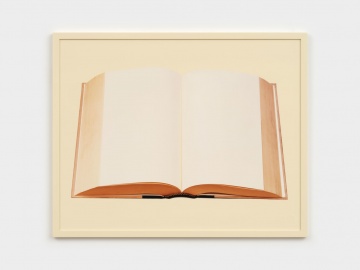

Both the finesse of Charlesworth’s seductive Cibachrome prints and her fascination with the iconography of desire were expanded in subsequent series, which often employed familiar motifs. Maintaining a focus on isolated images in saturated fields of color, from 1992 onwards Charlesworth’s photographs were composed and produced in her studio using the camera as a tool to conjure fantasies of her own imagination. For example, the cut-out image of an elusive Red Scarf from 1983 reappeared wrapped around a pair of heads in Red Veils (1992–93), and a thick red curtain is parted to make room for a telescope’s shaft in Untitled (Voyeur) (1995). In Pleasure of the Text (1992–93) Charlesworth invokes the use of silk in magic tricks by concealing an open book beneath a luxurious white scarf and suspending the composition against a black background. Presenting mysterious scenes imbued with unresolved intrigue, these works incite desire for the impossible.

Sarah Charlesworth (1947-2013) has been the subject of one-person exhibitions at a number of institutions including the major survey, “Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld,” at the New Museum, New York (2015), which traveled to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (2017); and a retrospective organized by SITE Santa Fe (1997), which traveled to the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego (1998), the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC (1998), and the Cleveland Center for Contemporary Art (1999). Her work is in important public collections such as the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; the Centre Pompidou, Paris; the Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven; and the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Charlesworth taught photography for many years at the School of Visual Arts, New York; the Rhode Island School of Design; and Princeton University.

[1] Sarah Charlesworth interviewed by Susan Fisher Sterling, March 23, 1997, in Sarah Charlesworth, SITE Santa Fe, 1997, p. 80

Robert Grosvenor

February 15, 2025 - March 22, 2025

An exhibition of recent sculpture and photography by Robert Grosvenor will survey his prolonged fascination with the aerodynamics of machinery. Since the 1980s, Grosvenor has applied his subtly elusive formal vocabulary to the vernacular of American car culture by transforming obsolete vehicles into inoperable sculptures. A series of exhibitions of uncannily altered vehicles isolated in striking or purpose-built spaces have frequently enshrined these works. Here, numerous sculptures are gathered under one roof in a lively installation that enhances their individual narrative qualities.

In the main room, a reflective deep purple sculpture is flanked with a vibrant green form on one side and a heavily rusted object on the other. Each work is a found object, perfected through small adjustments that enhance its existing form. The purple sculpture (Untitled, 2023) has no windshield and its headlights have been sprayed matte black, but it otherwise looks like it could be spurred into action. The green sculpture (Untitled, 2022) is smooth and pure, rocket-like, inanimately still. The rusted work (Untitled, 2022) was already romantically sculptural, the wooden planks of the truck bed aging like driftwood and its patina warm with wear. The machine still bears the name of its maker on its back, but the roof has been lowered to remove it completely from the realm of functionality. Arranged in a triangular formation facing the street with other smaller works surrounding them, the vehicles recall the gallery’s previous incarnation as a parking garage.

The front gallery contains a nautical sculpture (Untitled, 2023) stripped of its operative apparatus and leaning to one side. Painted in white and vibrant turquoise to accentuate its curves and points, the work is both familiar and ambiguous, imparting a distinct strangeness. On the surrounding walls are photographs of unlikely objects pictured against blue skies and green lagoons, complementing the sculpture in theme and tone. Some images depict vehicles and structures so characteristic of Grosvenor that one wonders if he made them himself. Animated with humor and vivid color, the photographs depict a compelling alternate reality.

Back to all Member Galleries

Back to all Member Galleries