Ortuzar

5 White Street

New York, NY 10013

212 257 0033

New York, NY 10013

212 257 0033

Founded by Ales Ortuzar in 2018, Ortuzar Projects is a gallery in Tribeca dedicated to promoting artists who have played a significant role in the development of 20th and 21st-century art but have not recently received critical exposure in New York.

Ortuzar Projects presents exhibitions in collaboration with artists, estates, foundations, and representing galleries, with the goal of providing expanded visibility and fostering renewed interest in artists’ work.

Artists Represented:

The Estate of Ernie Barnes

The Estate of Ernie Barnes

Matt Connors

Suzanne Jackson

Claudette Johnson

Jacqueline de Jong

Kurt Kauper

June Leaf

The Estate of Maruja Mallo

Ben Sakoguchi

Julia Scher

Linda Stark

The Estate of Anita Steckel

Joey Terrill

Takako Yamaguchi

BRIAN BUCZAK

BRIAN BUCZAK: MAN LOOKS AT THE WORLD

January 5, 2024 - February 17, 2024

BRIAN BUCZAK: MAN LOOKS AT THE WORLD

January 5 – February 17, 2024

Opening receptions: Friday, January 5, 12–6pm Gordon Robichaux, 41 Union Square West, #925 and #907 | 6–8pm Ortuzar Projects, 9 White Street

Ortuzar Projects and Gordon Robichaux are pleased to present Man Looks at the World, a solo exhibition of paintings, works on paper, and artist books by Brian Buczak (1954–87). Unfolding across both galleries’ locations, it is the artist’s first solo exhibition since 1989, following his untimely death from AIDS-related complications. Experimenting with appropriated pictures and poetic syntax, Buczak employed a variety of painting styles, reinterpreting childhood textbook illustrations, nineteenth-century academic painting, corporate logos, pornography, news media, and other found imagery to create a symbolic iconography that was, in his words, a “search for accidental significance.”

Motivated by his close correspondence and friendship with Ray Johnson, Buczak relocated to New York in 1976 from Detroit. He quickly befriended a largely older generation of artists involved in conceptual art, performance, and Fluxus, including Lawrence Weiner, Alison Knowles, Dick Higgins, Phillip Glass, and Geoffrey Hendricks, as well as elders Alice Neel and Louise Bourgeois, among others. Soon after meeting, Buczak formed a creative and romantic partnership with Hendricks that extended through the end of the younger artist’s life, leading to collaborations that spanned performance, assemblage, and the establishment of Money for Food Press. A small imprint headquartered out of their shared home—an 1820s townhouse that the couple painstakingly restored—the press published small edition artists books, through which Buczak cultivated a DIY sensibility and affinity for the juxtapositions created between pages. Concurrently, Buczak began using hand-cut stencils to create a lexicon of simplified forms that he would paint on storefront windows and in abandoned buildings across the city, spanning Buddhist flames and chalices, Masonic symbols and Greco-Roman figures. This repertoire also appeared repeatedly in his canvas works from the early 80s, in which he rhymes a diverse set of archetypal images across diptych and triptych compositions, as well as serial works on paper that mimic his experimental publications.

Hendricks has attributed the development of Buczak’s visual logic to his encounter with Rebus puzzles during the couple’s visit to Italy in the summer of 1977. These puzzles interweave illustrated pictures and individual letters to represent words or phrases, offering a key for how Buczak combinations of images were intended to manifest meaning greater than the sum of their parts. In the writing of longtime friend, artist Brad Melamed:

“Painting appropriated imagery was Buczak’s means of subverting what was already understood to be a mediated simulacrum of information. Like many of his peers in the eighties art scene, Buczak’s work was both cultural critique and an exploration of the politics of identity, but he expands his concerns into the metaphysical. He links his queerness with a notion of a multi-dimensional self …. For him the sacred and profane were to be uncategorized. Set free of their separation, Buzcak’s work opens the door to multiple readings that link pleasure and pain, knowledge and innocence, life and death: the phenomenological wonders of this world and beyond.”

Not unlike work by his Pictures Generation contemporaries, Buczak also employed cinematic devices such as close-ups, montage, and splicing, as well as the art historical references and formal eclecticism of Neo-Expressionism. In Broken Glass (Science Project Series) (1986–87), Buczak paints an image of a glass bottle being smashed by a hammer alongside a scene of a young boy swimming in water, creating a situation in which the feeling of jumping into cold water is formally and psychologically mirrored by the shattering glass. In the triptych Untitled (Martin Luther King) (c. 1985), he combines an impassioned image of Martin Luther King, a world map painted the black, red, and green of the Pan-African movement, and a vibrating field of electric blue and red. Moving left to right, the viewer experiences a shift from the specificity of a particular historical figure to an abstraction that may allude to a more universal sense of fervent emotion.

Though predating his AIDS diagnosis in 1986 and subsequent declining health, towards the end of his life Buczak began to focus on metaphysical subjects, including séances, ephemeral natural phenomenon, and ghostly landscapes, or what Hendricks refers to as the “spirit world.” Untitled (Phases of the Moon) (1986) portrays moments of astrological alignments between the sun, earth, and moon across four canvases, each linked to a corresponding season. In Buczak’s 1985 diptych Materialization, a group of figures sit in a circle, with one figures’ body repeating, as if through a glitch, across the canvases’ divide. This disjunction realizes a psychic orientation of pictorial space, suggesting the coexistence of the figure’s spirit in one dimension and the materialized body in another. This dislocation and formal distortion is often exaggerated by Buczak through his characteristic use of the vertical split in the diptych’s composition, a technique achieved by projecting images onto multiple canvases that—as explained by fellow artist friend and co-worker Andrea Evans—was inspired by his day job working on large scale industrial slide shows. In a rare description of his own work, Buczak speaks to the psychic dimension inherent to his process, stating, “my subjects appear to me in sleep, and the work is painted in a deep trance in total darkness.”

Brian Buczak (b. 1954, Detroit; d. 1987, New York) received a BFA in painting from The Society of Arts and Crafts in 1976. Solo exhibitions include Brian Buczak: A Memorial Exhibition, Emily Harvey Gallery, New York (1989); Brian Buczak: A Memorial Exhibition, Bound & Unbound, New York (1987); The Search for Accidental Significance, Pitt International Galleries, Vancouver (1987); The Lucy Stories, Printed Matter, New York (1985); VASE, J.N. Herlin, Inc, New York, 1982; and Corpse, Todd’s Copy Shop, New York (1982). Group exhibitions include Democracy: Aids, Group Material at Dia Art Foundation, New York (1988); Wall/Paper: 3 installations in an abandoned building (with Andrea Evans and Brad Melamed), Fashion Moda, New York (1981); The Page as an Alternative Space 1970–1981, Franklin Furnace, New York (1981); 9th St Survival Show, Charas at El Bohio, New York, 1981; Sound, P.S. 1 Contemporary Art Center, New York (1979); and Art Book Art, Detroit Institute of Arts (1979).

Thank you to the executors of the Geoffrey Hendricks and Brian Buczak Estate, Sur Rodney (Sur), and Hendrick’s children, Bracken and Tyche Hendricks. Since 2021, artists Andrea Evans and Brad Melamed––friends of Buczak since Detroit––have been serving as co-archivists of the artists’ legacies, providing invaluable insight into their work and life. The estates remain housed in Hendricks and Buczak’s former home, a Federal Style townhouse now celebrating its 200th anniversary. Restored by the artists from desolate conditions, the Greenwich Street façade is recognizable for the Lawrence Weiner text piece that adorns its façade, which reads: “Water Spilled from Source to Use.” Buczak’s correspondence with Ray Johnson was recently acquired by Northwestern University.

Ben Sakoguchi

Ben Sakoguchi: Belief & Wordplay

September 8, 2023 - October 21, 2023

Ortuzar Projects is pleased to present Belief & Wordplay, the gallery’s second exhibition with Pasadena-based artist Ben Sakoguchi (b. 1938, San Bernardino).

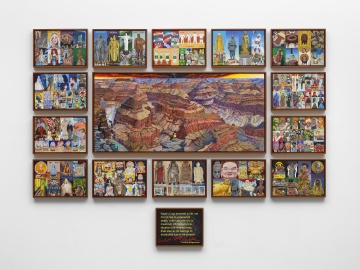

Totaling 94 canvases painted over the last five decades, the exhibition chronicles the complex, contradictory cultural landscape of the United States. Pairing the cheery pictorial style of commercial imagery with the often disturbing truths foundational to the country’s history, Sakoguchi mirrors a particularly American visual language and logic in which politics and entertainment are impossibly intertwined, and rationality is prone to devolving into pure affect. In ambitious multi-canvas works—such as Comparative Religions 101 (2014/2019), exhibited publicly for the first time—and durational series that can encompass hundreds of individual paintings, Sakoguchi untangles the thorny issues that undergird civilized society in a combination of social commentary and satire that is at once diabolical, illuminating, humorous, and macabre.

In his longest running series, spanning nearly fifty years, Sakoguchi creates small-scale paintings based on the composition and graphic design of vintage orange crate labels, which he observed in his parents’ San Bernardino Valley grocery store. The “Orange Crate Label Paintings,” with 56 examples represented in this exhibition, all adhere to the same rubric: each includes an orange, a fictitious brand, and a real location in his home state. This classically Californian brand of conceptualism, in which image and caption are paired in idiosyncratic juxtapositions, is used by Sakoguchi to respond to the endless minutiae reported in mass media. Two early paintings, for example, depict events in 1979: the Sandinistas’ overthrow of the US-backed Nicaraguan government, and the Greensboro Massacre, in which white supremacists and Nazis clashed with and killed protesting members of the Communist Workers Party. In retrospect, the overlap of these events on the timeline forces certain associations or patterns to emerge. While the web of events—from nuclear meltdowns to battles over abortion rights, arranged in a dense chronological grid—verges on the conspiratorial, Sakoguchi is keenly aware of the violent possibilities of ideology. Forcibly relocated and imprisoned in a Japanese internment camp during World War II, the artist is familiar with the hypocrisy and historical amnesia that accompanies shifts in social consciousness.

While his attentive documentation of historical events acts as a record made in real time, Sakoguchi also attends to more minor histories, whether it be the culture wars, waged simultaneously with the ballooning of the commercial art market; the history of baseball, or trends within popular music. In recent works the historic is often superseded by the viral, and his brands take on monikers from the near history of the Trump years, such as “Pussy Hat,” “Tiki Torch,” or “Pizzagate.” In a group of six “Quarantine Paintings” from 2020, rendered with a rare sparseness and sensitivity, Sakoguchi commemorates the Black Lives Matter movement and the lives of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and George Floyd. As a decades-spanning project, Sakoguchi’s “Orange Crate Label” paintings index the American news cycle, chronicling current events from the moment of their occurrence to their aftershock and eventual historicization.

In a parallel project, begun in the wake of the US invasion of Iraq, Sakoguchi evokes Francisco Goya’s Los caprichos (1797–1798). One group of twelve paintings, collectively titled “Star Spangled Banner” (2003–2004), presents the American flag as a divisive symbol of both liberty and injustice. Phrases from the national anthem, written in Spanish and English, are paired with brightly colored captions that cast their subjects in stark binaries, such as “incorrect/correct,” “do/don’t,” “bad/good,” “us/them.” Drawing out the absurdity that results from our country’s political polarization, the format was continued in the 2010s with the “Signs” series, which matter-offactly places signage wielded at opposing protests side by side. Instead of positioning one party or group over another, Sakoguchi acerbically critiques the universal follies and foolishness of contemporary American society.

The exhibition concludes with the sixteen-painting work Comparative Religions 101 (2014/2019). The center panel of the installation features a diminutive Albert Einstein sitting on the edge of the Grand Canyon. The scientist’s presence in the sublime landscape exemplifies the human desire to make sense of the vastness of the universe through religion, science, and philosophy. In addition to paintings that depict various spiritual figures, garments, statues, and relics, Sakoguchi extends the definition of religion to include the idol worship of celebrities and political figures. In doing so, he alludes to the human tendency to organize around a greater power, whether that be a religious or philosophical doctrine, fervent nationalism, or a Cheeto in the shape of Jesus Christ. Underneath the grid of paintings is a quote by Ludwig Wittgenstein, which perhaps offers a key into Sakoguchi’s ambiguous and nuanced position. It reads: “If we take eternity to mean not infinite temporal duration but timelessness, then eternal life belongs to those who live in the present.” In surveying but a glimpse of Sakoguchi’s persistent practice, the long present appears to extend endlessly in all directions.

Ben Sakoguchi received a BA and MFA from UCLA in 1960 and 1964 respectively. He was a professor of art at Pasadena City College from 1964–1997. Recent solo exhibitions include Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois, Paris (2023); Bel Ami, Los Angeles (2021); Ortuzar Projects, New York (2020); POTTS, Alhambra, California (2018); the Skirball Cultural Center, Los Angeles (2016); and Cardwell Jimmerson, Culver City (2012). His work has been featured in institutional surveys, including L.A. RAW: Abject Expressionism in Los Angeles, 1945–1980, Pasadena Museum of California Art (2012); The 46th Biennial Exhibition: Media/Metaphor, The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. (2000); Made in California: Art, Image, and Identity, 1900-2000, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (2000); and The Decade Show: Frameworks of Identity in the 1980s, New Museum, Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art and the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York (1990). His work is in the collection of The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Brooklyn Museum, New York; Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Cantor Arts Center, Stanford; Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge; and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C., among others.

Cynthia Hawkins

Cynthia Hawkins: Gwynfor’s Soup, or The Proximity of Matter

June 23, 2023 - August 11, 2023

Ortuzar Projects is pleased to present Gwynfor’s Soup, or The Proximity of Matter, the gallery’s first exhibition with Rochester-based artist Cynthia Hawkins (b. 1950, Queens, New York).

Through her ten new paintings, Hawkins has developed an improvisational process in which free-floating symbols, shapes, and fields of color are layered to occlude and veil each other in fractured planes. Appearing at once cellular and interstellar, the canvases seem to contain multiple compositions simultaneously, with varying spatial systems and color schemes that shift in and out of focus. The inspiration for her series has more banal origins, however: a photograph of tomato soup that a friend shared on social media. The interplay of overlapping beads of oil on broth, reflected light, and vividly saturated color initially appeared otherworldly to the artist, as the image was closely cropped enough for the soup to fill the entirety of the digital square. Amused and inspired by the reality of the images’ subject and the complexity of its composition, Hawkins has riffed upon its internal visual relationships in a continuation of her longstanding investigation of abstraction.

Returning to questions fundamental to her work of the 1970s and 80s, Hawkins’ new series employs grids and geometric systems to explore the spatial possibilities of painting. The paintings cut through a cross section of multiple planar realities, the results of her physical process at times resembling the methods of superimposition, layer modulation, and opacity play reminiscent of a digital environment such as Photoshop. Fields of contrasting colors warp around delineated forms to create curves, protrusions, and pockets from which bubbling orbs emerge. Like oil droplets swirling on the surface of soup broth, these distinct planes often abut one another like polar and non-polar molecules unable to bond. Globular forms, arrows, and invented symbols float freely across the surface, emphasizing a sense of movement and the potential for further transformation.

Throughout her career Hawkins has synthesized a commitment to abstraction and an interest in scientific concepts. Since the 1990s, her paintings have increasingly utilized imagery pulled from the observable world, her paint congealing into the almost-recognizable shapes of things–gesticulating organic forms that resemble cells under a microscope. In Gwynfor’s Soup, or The Proximity of Matter, Hawkins seems to prove that abstraction is already always all around us. Her new series illustrates how the intertextual relationships that emerge between contours, gaps, and fugitive forms are capable of constituting an ecosystem on the surface of the canvas that is very much alive.

Hawkins is a longtime teacher, scholar, and curator. She received her doctorate in American Studies from the University of Buffalo, SUNY with a dissertation titled, “African American Agency and the Art Object, 1868-1917,” and until recently she was the gallery director and curator at the Bertha V.B. Lederer Gallery, SUNY Geneseo, New York. She is the recipient of the 2023 Helen Frankenthaler Award for Painting and was included in the recent survey exhibition Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces, Museum of Modern Art, New York (2022). Hawkins’ solo exhibitions include Natural Things, 1996–99, STARS, Los Angeles (2022); Clusters: Stellar and Earthly, Buffalo Science Museum, Buffalo (2009); New Works: The Currency of Meaning, Cinque Gallery, New York (1989); and Cynthia Hawkins, Just Above Midtown/Downtown Gallery, New York (1981). Her work is in numerous public collections, including The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York; The Bronx Museum of the Arts, New York; and Kenkeleba Gallery, New York, among others. She lives and works in Rochester, New York.

Image: Cynthia Hawkins, Gwynfor's Soup, or The Proximity of Matter # 3, 2022, acrylic on canvas, 48 x 48 inches. Photo: Dario Lasagni

Takako Yamaguchi

Takako Yamaguchi: New Paintings

May 5, 2023 - June 17, 2023

Ortuzar Projects is pleased to present Takako Yamaguchi: New Paintings, the gallery’s first exhibition with Los Angeles–based artist Takako Yamaguchi (b. 1952, Okayama, Japan).

Yamaguchi’s ten seascapes, each sixty by forty inches, are rendered in oil and bronze leaf. Drawing on a diverse array of visual traditions from various parallel art histories, Yamaguchi has long sought to challenge the myth of an ostensibly race-neutral International Modernism through her work’s elaboration upon it with aesthetics of local, national, and ethnic identity. Since the 1980s, Yamaguchi has produced focused series that interweave motifs pulled from Japanese screens and kimono textiles with figures or styles derived from Western art movements, including 19th-century Romanticism, Mexican Muralism, and Art Nouveau. In this new series, the artist’s uniquely syncretic approach destabilizes the conventions of both European and Japanese landscape traditions, and through their collision, creates a dialogue between aesthetic frameworks historically at odds.

Yamaguchi’s paintings have periodically explored the idea of “abstractions in reverse,” an attempt by the artist to move against the current of 20th-century Western art history by traveling backwards in time, from pure abstraction toward illusionism. Arriving at a distinct visual language that resides in a space she calls “semi-abstraction,” Yamaguchi’s works cultivate a tension between naturalism, abstraction, and craft. With an awareness of precedents such as the Transcendental Painting Group–a constellation of artists active in 1930s New Mexico who arrived at a form of semi-abstraction that was influenced less by the European avant-garde than by Theosophy and their attempts to illustrate its spiritual ideas–Yamaguchi questions the historical dismissal of works that fail to arrive at abstraction through a purely formalist logic. Is this kind of work’s occupation of an indeterminate space simply a failure of nerve? As if in reply to this dead-end thinking, Yamaguchi’s folding together of incompatible aesthetic frameworks forms a new space for seemingly limitless experimentation and play.

A uniform horizon divides each canvas in two, separating the oceanic from the atmospheric. Despite the stark geometry that bifurcates her uniform canvases, the continual movement of water, from waves to vapor to clouds to rain, and the shifting times of day, undoes the regularity of Yamaguchi’s serial works. The artist further creates subtle gradation that imbue her richly saturated paintings with an illusionism that is in stark contrast to the bronze leaf that sits as a reflective surface on the painting’s substrate. A glowing metallic sunrise is interrupted by clean lines of stark white rain; a heavy downpour braids itself into rivers, unfurling into rivulets like unwound thread; a teal and turquoise sea meets a monochrome bar of sand. Natural elements like clouds, waves, and mountainous islands are made into recurring symbols; repeating like scales of fish, zig-zagging, looping, or braiding together. Moving between near-naturalism and something more akin to hard-edged painting, the elements variably recede into the picture plane or sit on top of each other, obfuscating the infinite horizon behind them, framing it, letting the viewer in.

Takako Yamaguchi received a BA from Bates College in Lewiston, Maine in 1975 and a MFA from the University of California, Santa Barbara in 1978. She has held recent solo exhibitions at as-is.la, Los Angeles (2022); Ramiken Crucible, New York (2021); Egan and Rosen, New York (2021); STARS Gallery, Los Angeles (2021); Cardwell Jimmerson Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (2010); Nevada Museum, Reno (2007); Kathryn Markel Fine Arts, New York (2007); and Jan Baum Gallery, Los Angeles (2006). She has been included in institutional surveys including The Ocean, Bergen Kunsthall, Norway (2021); With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972-1985, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles and Hessel Museum of Art, Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York (2019-2021); Transcendence: Abstraction & Symbolism in the American West, Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art, Logan, Utah (2015); California Echoes: Women Inspired by Nature, Orange County Center for Contemporary Art, California (2007); and L.A. Post-Cool, Museum of Art, San Jose, California (2002). Her work is in the collections of Nevada Museum, Reno; Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art; Long Beach Museum of Art, California; the Lynda and Stuart Resnick Collection, Los Angeles; and Deutsche Bank, New York, among others.

Image: Takako Yamaguchi, Loom, 2023, oil on canvas, 60 x 40 inches. Photo: Dario Lasagni

Back to all Member Galleries

Back to all Member Galleries