Modernism Inc.

724 Ellis Street

San Francisco, CA 94109

415 541 0461

Also at:

Modernism West

2534 Mission Street

San Francisco, CA 94110

415 541 0461

San Francisco, CA 94109

415 541 0461

Also at:

Modernism West

2534 Mission Street

San Francisco, CA 94110

415 541 0461

Over the past four decades, Modernism has presented more than 500 exhibitions, featuring an international roster of historical and contemporary artists. The museum-quality program, overseen by gallery founder and owner Martin Muller, includes conceptually challenging and aesthetically rigorous painting, photography, sculpture, video, performance art, and works on paper.

Since 1979, the gallery has been at the forefront of the art world, presenting a retrospective of the Russian Avant-Garde in 1980 – before any other West Coast gallery or museum showed the historically-important work of Russian Avant-Garde artists – and staging the first Bay Area gallery exhibition of Andy Warhol in 1982. Both abstraction and figuration have been central to the gallery program ever since. In addition to 17 more Russian Avant-Garde exhibitions, Modernism has shown the work of the Southern California abstractionist James Hayward since 1980, and recreated “Four Abstract Classicists”, a seminal 1959 Los Angeles County Museum of Art exhibition, in 1993. At around the same time, the gallery introduced America to the politically-charged conceptual works of Austrian-born multimedia artist Gottfried Helnwein.

In the 21st century, Modernism has continued to open new frontiers in the Bay Area art world. The historical program now encompasses Dada, Cubism, Surrealism, Vorticism, and German Expressionism, as well as the Russian Avant-Garde. Historical landmarks have included the first major West Coast retrospective of Le Corbusier in 2003, and the first major American exhibition of paintings, drawings, collages, and photographs by Erwin Blumenfeld in 2006. Over the past decade, Modernism has staged notable retrospectives of key modern artists including Edvard Munch, and historically important contemporary artists and photographers including Mel Ramos, John Register, Jacques Villeglé, and Judy Dater.

Representing nearly fifty contemporary artists from around the world, the gallery contributes to current artistic dialogues, both representational and abstract, with several dozen shows per year presented at both Modernism and Modernism West, as well as art fairs in North America and Europe. Areas of focus include conceptual and textual work, and art that meaningfully addresses important sociopolitical concerns.

The gallery regularly publishes books, monographs, catalogs, and fine art editions, including notable volumes about gallery artists Mel Ramos, Naomie Kremer, Gottfried Helnwein, Elena Dorfman, Charles Arnoldi, and Jacques Villeglé.

Artists Represented:

Alex and Mushi

Elina Anatole

Charles Arnoldi

Edith Baumann

Glen Baxter

Jean-Charles Blais

Lucien Clergue

Judy Dater

Elena Dorfman

Michael Dweck

Damian Elwes

Sheldon Greenberg

Philippe Gronon

Duncan Hannah

Gottfried Helnwein

Tony Hernandez

Scot Heywood

Raymond Holbert

Shawn Huckins

Bill Kane

Jerry Kearns

Jonathon Keats

Naomie Kremer

Eva Lake

Laurie Lipton

Peter Lodato

Kristine Mays

Lindsay McCrum

Yang Mian

John M. Miller

Alex H. Nichols

Andreas Nottebohm

Patti Oleon

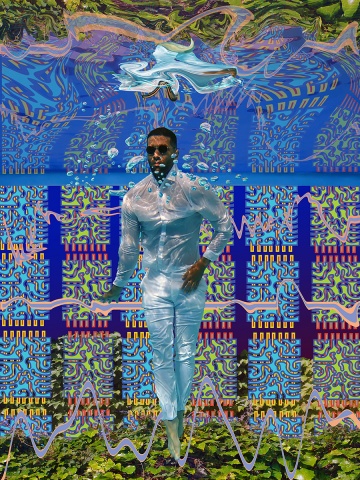

Agnieszka Pilat

Mel Ramos

John Register

Peter Sarkisian

Ben Schonzeit

David Simpson

Stephen Somerstein

Robert Stivers

Mark Stock

Sam Tchakalian

Mark Ulriksen

Jacques Villeglé

Stéphane Zagdanski

Works Available By:

Erwin Blumenfeld

Alexander K. Bogomazov

R. Crumb

Albert Gleizes

Ivan V. Kliun

Frederick Hammersley

Henri Hayden

James Hayward

George Koskas

Le Corbusier

Kazimir S. Malevich

Albert Marquet

Ilya I. Mashkov

Edvard Munch

Ivan A. Puni

Georges Valmier

Andy Warhol

Robert Wilson

Kirill M. Zdanevich

Modernism Gallery - Interior 2

Modernism Gallery - Exterior

Modernism Gallery - Interior

Eva LAKE

Relics of Beauty

February 12, 2026 - April 25, 2026

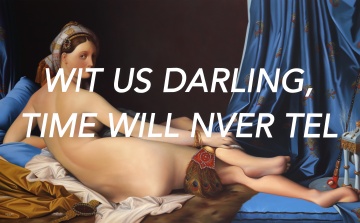

Modernism is pleased to present its second exhibition of collages by Eva Lake. In "Relics of Beauty," striking images are constructed from an array of art history and archaeology photography paired with pop-culture imagery of 20th-century women. The result is a body of work that rewrites the historical record with softness and femininity, and challenges the pervasive societal notions surrounding beauty.

Eva Lake’s collages are the natural culmination of her life and studies. She was a student of art history and archaeology at the University of Oregon and painting at the Art Students League of New York. Lake also spent decades working as a makeup artist and in the fashion industry. “In most of this work, I am uniting two lifelong pursuits: art history/archaeology and beauty/fashion,” she says. “I want to mix up the narrative of who is grand and who is pedestrian, of what is worthy of endless theories, and of what is dismissed as pretty for the idle moment.”

In the spirit of Hannah Höch [1889–1978] who appropriated and recombined images from mass media to critique popular culture, Eva Lake’s collages are saturated with cultural criticism. Rooted in scholarship and composed of archival imagery from publications such as "Gardner’s Art Through the Ages" (1926) and The Metropolitan Museum of Art's "Spanish Paintings: From El Greco to Goya" (1928), Lake’s deep understanding of this material allows her to produce a cutting cultural commentary that questions existing structures of power and sexism in the art world and beyond.

“When you look at ancient art, it's written about by men,” she says. “It was discovered and plundered by men. It was put into great museums like Berlin, Paris, London, and New York, by men. They are the ones that are documenting it, photographing it, and measuring it. And so I'm just trying to get in there. I'm trying to have the woman get a word in, edgewise,” explains Lake. “As always, I am trying to kind of feminize and do two things… I'm taking them down, and I'm bringing her up.”

This reclamation, or repatriation of sorts, is referenced in Lake’s collage "Greek Sculpture Helmet (Democracy on My Mind)." The woman, whose portrait was pulled from an Eastern European Cold War era magazine, is dressed in a helmet comprised of Elgin Marbles now held in the collection of the British Museum (a holding whose repatriation has been long debated). Lake takes the militant and softens it, but still returns to contemplation of morals and cultural injustice.

Another example of Lake’s encyclopedic art history knowledge at work is "Some Girls No. 15 (Face Fragment)," in which Lake references the partial face often seen in ancient sculpture. One of Lake’s favorite pieces of art is the Egyptian Face Fragment at The Metropolitan Museum. “Perfect. And priceless,” she calls it. “I wanted to create my own tribute to the beauty and the power of faces I have known through the media,” she says.

On view for the first time as a collection are works from Lake’s "Some Girls" series. Lake recalls the origin of this work: A friend offered me a book on Egypt I already owned, cut into and had my fill of. I thanked him and turned down the gift. That night as I lay in bed, I asked myself, “Well, what could I do with it, a second time around?” I saw myself tearing out pages and creating a grid. That’s it! In this fashion I could build a large collage. As this grid floated in my evening mindscape, one that is generally psychedelic in palette, I inserted glamorous female faces into the sheets. My mind was just playing but I quickly realized that it was riffing in the vicinity of the Rolling Stones’ "Some Girls" LP cover (by Peter Corriston and Hubert Kretzschmar). I started this body of work with the same electric colors as the record cover, collecting paper in the same color range, photographing it and then having it printed. For the initial "Some Girls," I began with Egypt but then ventured to other interests.

In the pursuit of feminine reclamation of male-dominated history, Lake takes the infamously reductive "Some Girls" LP cover (the band joked it was named as such because they could not remember the names of the girls pictured) and imbues it with iconic women. This group of works is also notable as it is the first time Lake has used her own photographs in an analog collage, yet another layer of reclamation.

Similar to Dora Maar [1907–1997] who disrupted and reimagined the female form and face in her photomontage and painting, Surrealism is also ubiquitous in Lake’s reconstruction of the female image. The exhibition’s outlier "Some Girls No. 23 (Lipstick Formation)" reveals such influences. “I was lucky to collect five large lips from the same makeup ad, different magazines,” she recalls. “Same photo really, just different lipstick colors. Instead of cutting out the lipstick, I decided what the hell, I am a makeup artist. Let this kind of power rule the skies!” declares Lake. The suspended lips evoke the isomorphism of Man Ray’s "The Lovers" (1936) and the Soviet era blimp. “This work reveals the three movements which made the most impact on me as a young artist (Pop, Surrealism, and the Russian Avant-Garde),” she continues. “Their precision and exuberance form the underlying foundation in almost everything I make—a hidden, buoyant order.”

Eva Lake has exhibited extensively in the United States and Europe since the 1980s. She is the recipient of multiple awards from the Oregon Arts Commission and The Ford Family Foundation. Her work is included in public collections such as the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and Portland’s Arts and Culture Council. She now lives and works in Portland, Oregon.

Jerry KEARNS

Zero-Sum

January 15, 2026 - March 7, 2026

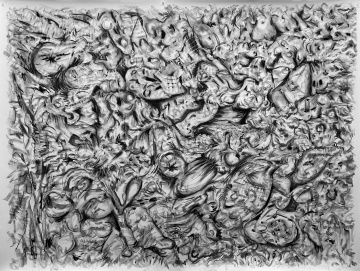

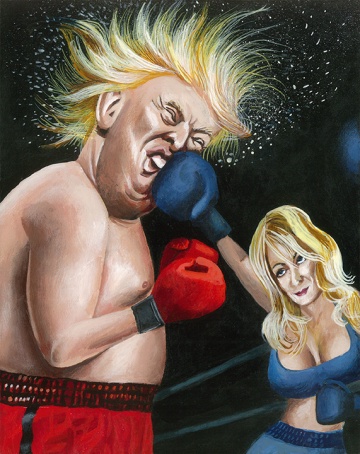

Modernism is pleased to present "Jerry KEARNS: Zero-Sum." The artist’s 11th solo exhibition with the gallery features six paintings and nine drawings, in which Kearns employs the ever-present vocabulary of popular culture, film, TV, cartoons, advertising, photographs, etc., to describe our reality where mediated information has replaced direct experience.

In a vein the artist dubs “Psychological Pop,” Kearns samples and repurposes the visual vocabulary which defines perception and shapes contemporary mythology. “I aim for psychological history paintings reflecting the time and place where we live,” he says. In a fashion similar to the early works of James Rosenquist and Andy Warhol, Kearns’s works strive for moral consciousness. And with a title like "Zero-Sum," it is evident that the cultural state Kearns portrays is that of a win-lose scenario.

Kearns’s recent paintings and drawings are a departure from the overt political narratives with concrete bipartisan positions in his early work, and a shift to a more nuanced examination of social issues that emerged as a byproduct of pervasive present-day political strategies for retaining power. Kearns’s work is no longer glaringly partisan, but contemplative of the divisiveness coming from every direction and the social breakdown that ensues.

“I want my art to tell stories about the reality I experience, hopefully, to share in shaping social meaning,” says Kearns. “During the time I was making the works in this show I was aware of a much more transactional mindset pervading public thought.” This transactionality is depicted rather literally in paintings like "The Dealmaker," where a finely dressed 1940s woman extends a stack of money, asking “This makes us even, right? Do you take cash?”

“While the need to connect and build relationships was as important as ever, the political culture was pushing us ever further into self-involved isolation,” explains Kearns. This isolation is manifested in Kearns’s lonely compositions which depict only a single subject each. In comparison to Kearns’s prior work, delightfully cacophonous and often teeming with multiple characters in vivid color, these new, mostly pastel, paintings and drawings, like the modern life, feel empty and void of connection. Ironically however, many of Kearns’s subjects seem to be mid-conversation with another person, via Roy Lichtenstein-esque speech bubbles, but with the other conversation participant not depicted, their actual existence becomes a question more than a reality.

The artist explains “The use of the 1950’s cartoons reflect my desire to locate personal / psychological dialogues that read as implications of long-term societal shifts away from the values of an earlier moment in America’s cultural history. The quieting of the compositions along with the pastel colors suggest memories of things gone by. The image becomes a dream-like echo of personal and societal loss."

The sentiment is seen in compositions like "Lady’s Man," where a lone gentleman rendered in graphite over a solid sage background is bent over in grief, contemplating "Why don’t you love me like you used to?" While the words feel romantic, the messaging is universal. “Sharing community, forming empathy for the other, was receding into the past,” says Kearns. “I tried to capture something of that loss in these paintings.”

Jerry Kearns has exhibited internationally across the Americas, Europe, and Asia since the 1980s. He has been featured many times in The New York Times, Art and Auction, ARTnews, and Artforum, among others. His paintings are included in many public and private collections, including the Museum of Modern Art (New York), National Galerie (Berlin), Brooklyn Museum (New York), the Art Institute of Chicago, Whitney Museum of American Art (New York), The Norton Family Collection (Los Angeles), San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, AMFA (Little Rock), and Queensland Art Gallery (Queensland, Australia).

Kristine MAYS

State of the Union

January 15, 2026 - March 7, 2026

Modernism is proud to present a selection of twelve poignant political sculptures in "Kristine MAYS: State of the Union." Reflecting upon the concept of DEI (Diversity, Equality and Inclusion) and its dismantlement in 2025, Kristine Mays examines the current political and social climate in the United States, exploring the nuances of race, war, power, intimidation, nationalism and identity. This body of work emerges from Mays’s grappling with ideas surrounding the betrayal of the “American Dream.” Witnessing the disconnect between national ideals and lived reality compelled her to create this vulnerable, raw, painful, and confrontational body of work.

Just as Robert Rauschenberg employed the American flag to interrogate national identity and politics in works such as "Signs" (1970), Mays created "This Is America," an American flag constructed of wire, with beads hanging from its frayed edges representing blood and tears.

Sculptor Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi designed the Statue of Liberty to represent ideals of equality, democracy and freedom. Mays presents "Birthing Greatness" as an optimistic expression anticipating the change-makers that will soon shape the world.

Sculpting simple human forms, much like Keith Haring’s faceless figures that reveal no hint of gender, race, religion or sexual orientation, Mays’s "Human Complacency" includes everyone as she confronts our involvement in the issues unfolding in the country.

Employing a unique sculptural method, Mays bends and hooks rebar tie wire together with pliers, one piece at a time. Each piece requires at least sixty hours of labor, during which she gives form to a human body or garment without reliance on a mold or model. Especially remarkable are the gestural qualities that make the works appear both animate and soulful. “I am breathing life into wire,” she says. “With each work, I create a form that reveals the essence of a person and that speaks to humanity as a whole.” Quotations accompanying her sculptures often provide important context for full appreciation of their content.

In the words of Nina Simone (American singer, pianist, songwriter and civil rights activist), “An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times.” Mays does exactly that, offering a harrowing but hopeful portrait of the state of the union.

San Francisco native Kristine Mays has exhibited across the country since 1993. Her work is held in the collections of the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture (Washington D.C.), The Arkansas Museum of Fine Art (Little Rock), and the Crocker Art Museum (Sacramento). Mays was the Grand Finale Winner of the 5th Annual Bombay Sapphire Artisan Series National Competition in 2015. She was the artist-in-residence at the Bayview Hunters Point Shipyard in San Francisco 2011-2013. She has also served on the Board of Directors for ArtSpan and participated in the San Francisco Open Studios program for over 20 years. Seeking to create impact and change with her art, Mays has participated in raising thousands of dollars for AIDS research through the sale of her work by collaborating with organizations like Visual Aid, the San Francisco Alliance Health Project and WE-Actx.

Group Show

Second Nature

September 4, 2025 - November 1, 2025

FEATURING: ALEXANDMUSHI, UTA BARTH, LAUREN BARTONE, MICHAEL BRENNAN, DEBORAH BROWN, GORDON COOK, EDWARD CURTIS, JUDY DATER, ELENA DORFMAN, ALAN DRESSLER, MICHAEL DWECK, DAMIAN ELWES, SHELDON GREENBERG, EMANUEL GYGER, JAMES HAYWARD, WADE HOEFER, SHAWN HUCKINS, JERRY KEARNS, SAMEH KHALATBARI, NAOMIE KREMER, LOUISE LEBOURGEOIS, KRISTINE MAYS, LINDSAY MCCRUM, JOHN NAVA, ROBERT PARKEHARRISON, SARAH PERRY, ANDRÉ RACZ, MEL RAMOS, JOHN REGISTER, MICHAL ROVNER, NAOMI ALESSANDRA SCHULTZ, CAMILLE SOLYAGUA, ALBERT STEINER, MARK STOCK, HIROSHI SUGIMOTO, SAM TCHAKALIAN, DAVID TROWBRIDGE & HELENA CHAPELLIN WILSON

Nature has arguably been the favorite subject of artists since the beginning of time. While some artists dedicate their practice to portraying the natural world as it appears with accuracy, others use nature loosely as a muse or starting point to employ their artistic processes. In today’s world where we are inundated with content of nebulous artificiality, questioning "is this real or fake" has become second nature. While artists continue to use nature as a subject and inspiration, the question "is this nature or is this a product of a human intervention" feels more pertinent than ever when viewing art and imploring so feels instinctual.

Modernism is pleased to present "Second Nature," a group show of 50 artworks from 1900 to contemporary, which explores the indeterminate boundary between the organic and the constructed. The exhibition brings together works that appear to authentically depict nature with seemingly blatant manipulations of the natural world. As the organic is transformed and artificial compositions mimic nature, "Second Nature" invites viewers to reconsider the divide. What appears raw may be refined and what seems fabricated, unexpectedly true to nature.

The conundrum lies within the art itself, as the appearance of the work often does not reveal the truth of its authenticity. For example, Hiroshi Sugimoto’s "Devonian Period" seems to be a genuine black and white photograph of coral reef. The viewer would likely believe so, unless they were aware the image is from his "Dioramas" series, a body of photographs taken of museum exhibits. What appears to be a live and bustling ocean floor is actually a still display of marine life replicas behind glass, not submerged in water. While seemingly more real than the colorful flora scene of Damian Elwes’s "Amazon Cloud Forest," one could argue that Elwes’s depiction of nature, while stylistically expressionist, is closer to real nature. Created in response to the colors of the exotic vegetative landscape he experienced when hiking a volcano in Colombia, Elwes’s composition is only once removed from the original. Sugimoto’s, on the other hand, is twice removed from its original, since the photograph is a depiction of a depiction of nature. Complexities such as these are dissected throughout the exhibition.

Perhaps then we can only consider depictions of nature once removed as natural. In doing so, we would look to the sober landscapes of John Register. Both "Hanalei Bay" and "Study for Further Lane" present as earnest scenes of American Realism, taken from real places in the world. However, when we consider Register’s signature process of meticulously redacting nonessential visual information to produce a more simplified distillation of the original subject, the viewer is left to wonder how true to nature his landscapes really are. Similarly, the two soft-focus photographs from Uta Barth’s "Ground" series featured in the exhibition present natural landscapes, but with so much detail blurred, the classification as real nature feels complicated.

The tightly cropped composition of Mel Ramos’s watercolor "Salou," which depicts the underside of fronds of two palm trees, is rendered in such detail that categorization as organic nature seems probable. But even if "Salou" was composed from a photograph or was a genuine plein-air study, the sterile state of the two trees hardly coveys "natural," rather, a man-made and regularly manicured paradise resort. Without the context of their surroundings the viewer is left to speculate.

Some works in the exhibition erode the original context of natural forms to such a degree that they no longer read as nature despite being so conceptually rooted in it, like Sameh Khalatbari’s "Fly of a Lifetime" and Naomi Alessandra Schultz’s "Still Life with Clippings and Waste Bin." The deconstructed depictions of pastoral scenes by Shawn Huckins and Michael Brennan, though rendered with masterful realism, border surrealism in their composition and the mind refuses to compute them as natural.

Other works also modify organic forms but they still read as nature. The digitally stitched photographic tapestries of Lindsay McCrum and Elena Dorfman are clearly of human invention, but their natural origins remain undeniable.

In addition to manipulating nature in form, artists in the exhibition also manipulate nature as material. In "Transmutations 1" Dorfman incorporates metals and minerals native to the places pictured in her photographs to root the work in the land it originated from and to explore the relationship between human and nature. Lauren Bartone utilizes organic material like fustic wood and the cochineal insect to dye the linen used in "Empire."

Other artists in the exhibition also use raw nature as material such as Naomi Alessandra Schultz in her installation piece "Flagged Hedge" composed from branches and David Trowbridge’s wall sculpture "Psalm #144" crafted partially from a tree. Is it possible organic matter as material is the closest we can get to an actual representation of nature? Or does the act of alteration automatically render it unnatural?

Other works in Second Nature propose the possibility that human intervention does not inherently make depictions of nature unnatural. After all, aren’t humans, after stripped of their modern adornments, organic forms? Amongst the nature-or-not paradoxes present in the many of the other works in the exhibition, artworks featuring humans, even though posed, may seem to be the most natural of all. Judy Dater’s "Self-portrait with Petroglyph" reads prehistoric. Michael Dweck’s "Mermaid 162, Aripeka" reminds us of the inseparability of human and nature and ALEXANDMUSHI’s "Two Chairs, Giant Rock, Joshua Tree," our position in relation to it.

Or perhaps nature simply cannot truly be portrayed representationally at all and every depiction is inherently artificial. In painting a bird, like Jerry Kearns’s "SWOON," it ceases to be a bird. While airborne, Kristine Mays’s sculptures do not become any more real than a bird painted on canvas. Does the process of recreating an image from the natural world, only cause further separation from the organic form it represents? Is every depiction of nature a simulacrum? If so, nature cannot be conveyed authentically with visual forms. Perhaps the truest portrayal of nature in art is nonfigurative and Naomie Kremer’s enveloping canvases of gestural abstract marks, inspired by nature, yet still abstract, may be the closest we can achieve to the actual experience of nature.

Through material, process, and form, artists in "Second Nature" create confounding contradictions: natural but not, nature but also artificial. In portraying the natural world, rather inauthentically, a sort of “second nature,” i.e. not the original, now once or even twice removed, emerges. And asking the question "is it nature or not" is only second nature.

Text and exhibition curation by Asa Perryman

THE PUBLIC IS INVITED TO AN OPENING RECEPTION ON THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 4TH FROM 6:00-8:00PM

Gallery Hours: 10am-5:30pm Tuesday-Saturday

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CALL: 415-541-0461 OR EMAIL: INFO@MODERNISMINC.COM

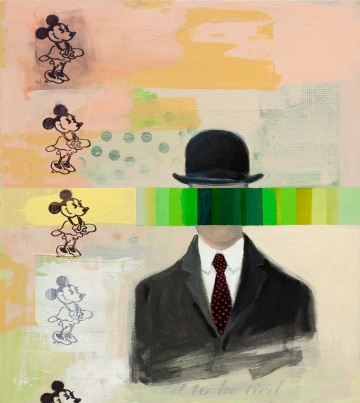

Sheldon GREENBERG

Syncretic Overlays

August 22, 2025 - January 10, 2026

Modernism is pleased to present seven paintings and nine works on paper by Sheldon Greenberg in "Syncretic Overlays." Reminiscent of Robert Rauschenberg, Greenberg appropriates familiar iconography to pay homage to masters who have shaped artistic expression and to explore how their influence resonates in contemporary practice.

The paintings borrow imagery from Old Masters such as Jean Siméon Chardin’s "Boy with a Spinning-Top" (1738) and Modern Masters like Edgar Degas’s "Race Horses" (c. 1885-1888), Gustav Klimt’s "The Kiss" (1908), Henri Matisse’s "Large Reclining Nude" (1935), and Balthaus’s "Les Enfants Blanchard" (1937) and "Thérèse sur une banquette" (1939). Having admired these historic paintings for decades, Sheldon Greenberg wonders whether they might gain new admirers if they were to be reconceived as contemporary art. In pursuit of this question, Greenberg critically broke down what he saw and systematically reconstituted the most fascinating elements in his own contemporary style.

The works on paper offer us insight into Greenberg’s process. While at first glance many appear seemingly abstract, peering through translucent layers of color, the images obscured beneath almost become visible and the artist’s method of redacting visual information to create a more complex amalgamation is revealed.

As eclectic as these works may be, Greenberg has unified them through his use of visual devices carried over from his previous bodies of work. Principal among these are his use of silkscreens, stripes, polka dots and mute charts. The silkscreens are especially important on both a visual and conceptual level. Often taking Greenberg’s photographs of palm trees as their subject, they provocatively disrupt the traditional spatial organization of paintings from past centuries, in addition to distorting the viewer’s sense of time, as they employ a photographic process that didn’t exist in the era of Chardin.

Named after well-known songs from pop culture, Greenberg’s paintings recontextualize landmark works from the canon to offer the viewer an opportunity for a postmodern reconsideration of the works’ cultural, personal and temporal meanings.

Sheldon Greenberg was born in Shreveport, Louisiana in 1956. He studied at the Art Students League in New York from 1985-86 and received an MFA from California College of the Arts & Crafts, Oakland in 1994. His work has been shown across the nation and at museums including the de Young, the San Diego Museum of Art and the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento. Greenberg has taught painting at The Academy of Art in San Francisco since 2003. He now lives and works in Oakland, California.

THE PUBLIC IS INVITED TO A RECEPTION FOR THE ARTIST TUESDAY, OCTOBER, 21, 6-8PM

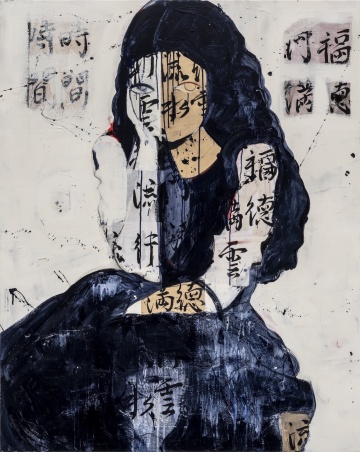

Helen Kim

Story Lines

August 22, 2025 - October 25, 2025

Modernism is pleased to present seven paintings and nine works on paper by Sheldon Greenberg in "Syncretic Overlays." Reminiscent of Robert Rauschenberg, Greenberg appropriates familiar iconography to pay homage to masters who have shaped artistic expression and to explore how their influence resonates in contemporary practice.

The paintings borrow imagery from Old Masters such as Jean Siméon Chardin’s "Boy with a Spinning-Top" (1738) and Modern Masters like Edgar Degas’s "Race Horses" (c. 1885-1888), Gustav Klimt’s "The Kiss" (1908), Henri Matisse’s "Large Reclining Nude" (1935), and Balthaus’s "Les Enfants Blanchard" (1937) and "Thérèse sur une banquette" (1939). Having admired these historic paintings for decades, Sheldon Greenberg wonders whether they might gain new admirers if they were to be reconceived as contemporary art. In pursuit of this question, Greenberg critically broke down what he saw and systematically reconstituted the most fascinating elements in his own contemporary style.

The works on paper offer us insight into Greenberg’s process. While at first glance many appear seemingly abstract, peering through translucent layers of color, the images obscured beneath almost become visible and the artist’s method of redacting visual information to create a more complex amalgamation is revealed.

As eclectic as these works may be, Greenberg has unified them through his use of visual devices carried over from his previous bodies of work. Principal among these are his use of silkscreens, stripes, polka dots and mute charts. The silkscreens are especially important on both a visual and conceptual level. Often taking Greenberg’s photographs of palm trees as their subject, they provocatively disrupt the traditional spatial organization of paintings from past centuries, in addition to distorting the viewer’s sense of time, as they employ a photographic process that didn’t exist in the era of Chardin.

Named after well-known songs from pop culture, Greenberg’s paintings recontextualize landmark works from the canon to offer the viewer an opportunity for a postmodern reconsideration of the works’ cultural, personal and temporal meanings.

Sheldon Greenberg was born in Shreveport, Louisiana in 1956. He studied at the Art Students League in New York from 1985-86 and received an MFA from California College of the Arts & Crafts, Oakland in 1994. His work has been shown across the nation and at museums including the de Young, the San Diego Museum of Art and the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento. Greenberg has taught painting at The Academy of Art in San Francisco since 2003. He now lives and works in Oakland, California.

Group Show

Selected Abstract Works

July 17, 2025 - August 22, 2025

Modernism is pleased to present a selection of 11 paintings by contemporary Modernism artists addressing a range of ideas, all expressed with an abstract vocabulary.

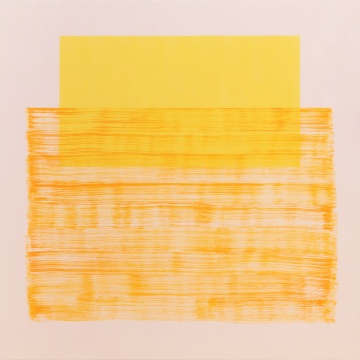

The exhibition includes work from living artists, both new and familiar, ranging from long standing cornerstones of the gallery’s programming, like James Hayward and Naomie Kremer whose history with Modernism harks back to before the turn of the millennium, to very recent additions to the roster such as Sameh Khalatbari and Victor Reyes. Though connected by the loose thread of abstraction, the works range from the formal abstraction of Edith Baumann to the lyrical abstraction of Macha Poynder. In the exhibition, white monochrome paintings are juxtaposed with compositions of explosive color. Monumental paintings that tower over and envelop the viewer neighbor small works that invite the viewer in for closer examination.

The exhibition’s contrasts are not only aesthetic, but conceptual as well. Works, like those of Charles Arnoldi, focus on iterative visual qualities and the correlative experience of form and color, while others symbolize nonfigurative narratives. Some narratives are political such as Sameh Khalatbari’s "1401 N/m2 Resistance – No.1 Resistance," a large-scale mixed media painting created in response to the death of Mahsa Amini and the ongoing conditions of gender apartheid in Iran. In this work, bands of bound cord are restrained and reshaped by the physical tension of opposing cords, symbolic of the Iranian women Khalatbari represents in her work.

Other narratives are socio-anthropological like Victor Reyes’s enormous diptych "Silent Hart of the Earth" which recalls the San Francisco of decades past and tells the story of its jarring convergence with the ever-changing city of present day. The layered forms, created by a meticulous sequence of screens and molds, echo the multi-layered personality of the place by which it was inspired.The abstraction of place and memory does not end with Reyes. Naomie Kremer translates personal experiences and observations of nature, into a visual language that makes the real unrecognizable, echoing the processes of Ellsworth Kelly and Brice Marden.

Like Naomie Kremer, Edith Baumann’s paintings also are personal, though they are not self-referential. Much like Mark Rothko, Baumann utilizes economy of means in her zen-minded minimalist paintings, beckoning the viewer not to ponder the artist, but the self.

In contrast to the simplicity of Baumann’s formal abstraction, Hayward’s topographically rich gestural impasto paintings embrace the lyrical abstraction of Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, but with the austerity of ivory hues.

The inclusion of such diverse work presents a brief continuum of Modernism’s history in presenting the abstract. From Modernism’s conception and very first exhibition, abstraction has served as a primary pillar of the gallery programming. Whether formal or lyrical, vibrant or muted, large or small, Modernism is proud to celebrate the nonobjective in all its variety.

Alex H NICHOLS

SHOCK whisper

May 22, 2025 - July 31, 2025

Modernism is pleased to present "SHOCK whisper," an evocative new series of paintings and installation by artist Alex H Nichols. Rooted in introspection and vulnerability, Nichols’ work explores the fragmented nature of memory, identity, and recovery—inviting viewers into an intimate process of reconstruction and self-discovery.

Through bold yet gentle gestures, Nichols weaves narratives of personal and collective histories. Her paintings begin as fragments—fragments of sentences, fragments of form, fragments of self—and build toward an elusive wholeness. She describes her process as retrieving pieces of herself, creating a world of Indigo. Using a limited palette of ultramarine blue, burnt umber, mars black, and powdered charcoal to plunge into deep, contemplative spaces. Black inside blue. Brushing blue, the excess water falls downward evoking the sensation of memory rising and falling, expanding and contracting, as she confronts the quiet truths of her past.

Nichols’ paintings confront questions of trauma, recovery, and psychological safety: "When I am in shock, I need a space where I can retrieve myself," says Nichols. “Why blue? Blue is the blue rug of my childhood cast in moonlight when everyone is asleep, blue in my childhood is imagination, blue is safety.”

In "SHOCK whisper," viewers encounter not only the visible figures and shapes that emerge from her canvases but also the hidden, internal landscapes they represent. Nichols uses the rich symbolism of blue—reminiscent of the blue rug cast in moonlight from her childhood evoking imagination, dreams, and safety—to create a space of refuge, a contemplative arena for soul retrieval. Here, art becomes a tool for individuation, echoing shamanic traditions and Jungian psychology.

Join us at Modernism West to explore this profound exhibition that asks us all: “how do we gather the fragments of ourselves after shock, whether personal or political, and how do we rebuild?”

THE PUBLIC IS INVITED TO A RECEPTION FOR THE ARTIST THURSDAY, MAY 22, 6-8PM

Helen Kim

Elasticity of Color

May 8, 2025 - July 9, 2025

As a youth, Helen Kim was intrigued by the beauty of the art on display. Set high on the wall above the chalkboard, the twenty-six drawings were unlike anything she’d ever seen growing up in Korea. Learning that the drawings were the alphabet, she was elated, and even more delighted when she learned to draw the letters for herself. “When I eventually learned cursive, I was lauded for my beautiful penmanship,” she recalls. “It felt like I was drawing.”

Decades later, handwriting remains central to Kim’s artistic practice, an essential dimension of oil and cold wax paintings that contain layers of inscrutable lettering in conversation with saturated color fields. Modernism is pleased to present 39 recent works in "Elasticity of Color," on view from May 8th to July 9th.

In addition to the memories of the alphabet, Kim is deeply influenced by the material world of her childhood. She was especially taken by the vibrant colors of traditional Korean clothing, and the saturated hues of silk gift pouches containing money or jewelry, as notable for the ornate designs of the fabric as the objects they contained. She recalls the bright colors of persimmons, apples and pears, set out on ceremonious occasions. “I was intrigued by the offset, repetitive pattern of the organic shapes.”

Inspiring the title of this exhibition, these memories and colors are embedded in her paintings, often reflected in names such as "Persimmons" and "Hopscotch." Even if the viewer is unfamiliar with the specifics, the specificity of the memories is apparent, and leads the viewer to vicariously experience the artist’s feelings and thoughts, past and present.

Like memories, the paintings have many layers. Kim begins with a single color. After applying a field of paint to the panel, she draws with oil sticks, often inscribing unprompted words that come to mind. Frequently drawn with her non-dominant hand, the letterforms serve as the first move in a visual puzzle that Kim works through by alternate layers of color and line until a solution is reached.

The result is a sort of palimpsest replete with pentimenti. Kim sees the process as “about the interpretation, exploration and execution of an idea,” every stage of which is preserved in the depth of oil and cold wax. Kim’s training as an architect informs her process and the crossover between art and architecture is apparent in her work. In each painting, Kim builds a visual world through the give and take of personal marks, discovering novel structures to scaffold her past.

Kim uses various mediums- paint, drawing and knitting- to recall memories into the present. In works such as "Stockinette," she knits compositions that stand beguilingly between two and three dimensions. Even before she mastered the alphabet, Kim learned knitting from her maternal relatives. “I remember the common bond, and the meditative feeling that came from the repetitive motion of connecting loops,” she says. “The linear process is the same for knitting and painting, both of which create complexity through layers of color.”

The complexity lies beyond the reach of words. “My life’s stories are visually narrated and abstracted in my paintings and knitting,” Kim explains. “These memories and events, which have shaped who I am, are the conceptual catalyst for my art.”

THE PUBLIC IS INVITED TO AN OPENING RECEPTION ON THURSDAY, MAY 8TH FROM 6:00-8:00PM

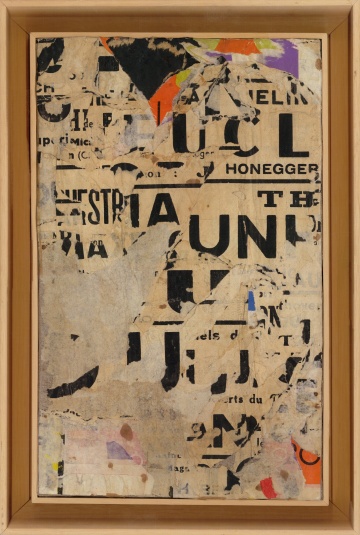

Jacques VILLEGLÉ

Urban Language

May 8, 2025 - June 9, 2025

Modernism is pleased to present its ninth survey of seminal French contemporary artist Jacques Villeglé [1926-2022]. "Jacques VILLEGLÉ: Urban Language" examines twenty-five décollage masterpieces by this influential Nouveau Réaliste, through the lens of typography.

EXCERPTS FROM "JACQUES VILLEGLÉ AND THE STREETS OF PARIS" BY BARNABY CONRAD III

<< Villeglé spent most of his life wandering the streets of Paris, pulling torn advertising posters off the ancient walls and pronouncing them Art. "In seizing a poster, I seize history, he says. "What I gather is the reflection of an era."

Born in Brittany in 1926, Villeglé was a seventeen-year-old architectural apprentice in Nantes during the bleak days of the German Occupation. After the Liberation in 1944, he moved to the City of Light, where he was drawn to filmmaking, avant-garde Lettrist poetry, and painting. The prewar art movements of Cubism and Surrealism had melted into abstraction, but Villeglé’s earnest attempts at Art Informel soon struck him as redundant, and he destroyed his canvases. Without a job and at loose ends intellectually, he became a "flâneur," a curious intellectual roaming through war-scarred Paris. “As I walked through the streets, I was struck by the color and typography of the posters. In those days, the cinema and concert posters rarely had images—just words—and they had been torn and shredded to where they became something else, with a post-cubist look to them. I began to see them as paintings made by anonymous hands.”

Villeglé recalled, "Even as a young student, I was always interested in typography.” In early 1940s France, Villeglé attended an exhibition of prewar posters by Paul Colin, Jean Carlu, Cassandre, and other artists at the Galerie Charpentier opposite the Palais de l'Élysée. “I could see that the poster artists had a dialogue with the cubist painters of their time. Most fascinating for me was the poster typography, the lettering itself. Months later, I returned to that gallery and bought the exhibition catalogue.” Villeglé kept this catalogue in his possession up to his passing.

An avid reader, Villeglé was poking around a bookstore one day when a book caught his eye and he bought it on sale for a few francs. It was poet Blaise Cendrar's novel "La Fin du monde, filmée par l'Ange N.D.," illustrated by Fernand Léger. "The text was printed in a font used in foreign posters actually, Cheltenham gras—and Léger's illustrations were in primary colors," he recalled. "I was amazed to see this book had been printed in 1919. It seemed so modern, so fresh. It made me want to do something in the art world that was this bold."

“After the war, I learned that posters inspired Stéphane Mallarmé for his poem 'One Toss of the Dice Will Never Abolish Chance.' Mallarmé was the pure poet. He composed his poems thinking about the compositions of posters for theater and advertising. I also knew that Georges Braque introduced letters into his cubist paintings, like 'Le Portugais' in 1912. Early on I believed that letters gave structure to posters on an abstract level, and I looked for that in the posters I took.”

In 1949, Villeglé and his then artistic collaborator and life-long friend, Raymond Hains [1926-2005], began scavenging advertising from billboards on the grand boulevards, snatching political posters in the financial district, and pillaging Left Bank walls plastered with flyers for jazz concerts and art exhibitions. Mounting them on canvas, they presented them as a new kind of art. Between 1949 and 2003, Villeglé himself plucked more than 4,500 works from all twenty of Paris’s arrondissements, carefully labeling each with the exact date and street address of the poster’s origin. Each work became a unique time capsule of the ever-changing city.

This selective collector of torn posters casually explained his impulsive modus operandi: "These are very rapid decisions. François Mauriac once said you should write like a sleepwalker. Was it the same for me with posters? If you see something in the street, you have no time to meditate. You strike fast, like a photographer, in less than a second, and worry about it back in the studio."

Villeglé's collecting habits may have been impulsive, but early on he understood that he had tapped into an enormous river of expression. "I realized right from the start that lettering would change, that new colors would be developed, that photography would be employed someday. Electric blue didn't exist, for instance. So right from the beginning I saw this material would be historic and would constitute an archive, a ragged memory of our era."

Such a time capsule of typography, "Les Dessous du Quai de la Rapée," 21 mai 1963, appears to be an alphabet composed of tipsy, deformed letters. At the top of the picture, the words "Beaux-Arts" have been torn to spell "Faux Arts" - fake arts. Further observation reveals fragments of concert announcements for Beethoven, Rossini, Mozart, De Falla, and even Gershwin's "Porgy and Bess" and "An American in Paris." The letters bob in a cacophonous universe that evokes the Lettrists' typographical obsession and such Russian avante-garde artists as Iliazd (Ilya Zdanevich).

The Lettrists said that poetry was made not simply of ideas or words, but of letters that could be scrambled and manipulated into new words and sounds. Villeglé and Hains went a step further: they saw that letters were ultimately graphic elements that could be distorted by human hands, whether through torn posters or by a camera lens.

In 1953, Hains and Villeglé used Hains's hypnagogoscope (an original camera invention which abstracts images and words) to distort Camille Bryen's 1950 tone poem, "Hepérile," into strange, otherworldly shapes that twisted and slithered across the page like an indecipherable chameleon alphabet. No one could read it, but it was interesting to look at. They printed it as a small book in a limited edition. Titled "Hepérile éclaté," it became a hit in avant-garde circles. Even the great cubo-futurist typographer "Iliazd" (Ilya Zdanevich) got hold of a copy and raved about it. In a text circulated at that time, Villeglé wrote, "Les Lettristes ont fait éclater le mot, Les Hepérilistes font éclater la lettre" (The Lettrists shattered the word, the Hepérilists shatter the letter.) >>

Villeglé’s work reads like a palimpsest—found, effaced and recontextualized. Inspired by Mallarmé’s spatial poetics, Léger’s bold modernism, and the Lettrists’ deconstruction of language, Villeglé used typography not as a medium to express meaning, but as material, abstract yet archival. Torn type, disjointed letterforms, and unintended alignments erode syntax so that a letter becomes more than a component of a word, and instead a visual historical record.

Jacques Villeglé’s work has been exhibited extensively in the United States and Europe, and is the collections of many important museums worldwide (Museum of Modern Art, New York; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Detroit Institute of Arts; Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; Tate Gallery, London; Moderna Museet, Stockholm; Musée d’Israël, Jerusalem). In 2008 a major retrospective of his works was exhibited at the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. In 2011 Modernism published "Urbi et Orbi," the English translation of Villeglé’s 1959 theoretical writings. Major monograph "Jacques Villeglé and the Streets of Paris," authored by Barnaby Conrad III, was published in 2022, also by Modernism.

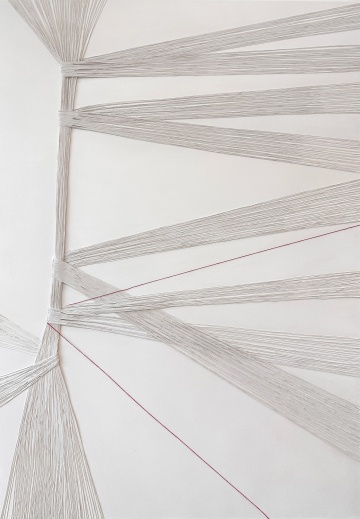

Naomie KREMER

Duende

March 6, 2025 - April 26, 2025

When Naomie Kremer approaches a blank canvas with a loaded brush, she cannot predict the first move she’ll make. She takes a deep breath. She raises her arm. She presses glistening bristles against smooth white linen to make a mark. Departing from this arbitrary point, she forms a line.

The act is pure impulse, drawing on decades of practice. Though necessary, dexterity is not sufficient. “I have to pay close attention to when the impulse ends,” she says. “I have to recognize where it needs to be nurtured and coaxed to its natural conclusion.”

An apt word for this creative act is "duende." Originally used in relation to flamenco, the term was most memorably defined by the great Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca, who called it “a momentary burst of inspiration, the blush of all that is truly alive, all that the performer is creating at a certain moment.” Duende is the essence of performance at the highest level, whether on the guitar or with a paintbrush.

In the spirit of Garcia Lorca’s writing and in recognition of Kremer’s performative approach to painting, Modernism is pleased to present "Duende," a selection of fifteen paintings and one video that show the artistic power of impulse guided by flawless technique grounded in conceptual ingenuity and theoretical rigor.

Kremer first started to grapple with the theoretical problems underlying this new body of work while studying art history at Sussex University. Reading Wassily Kandinsky’s "Point and Line to Plane," Kremer discovered an approach to abstraction premised on linear dynamism. The dynamism Kandinsky described coincided with her way of creating abstract spaces through movement. What distinguishes the current work conceptually, she explains is that she’s conjuring “stories and events within those places.” She conjures them instinctively, not fully knowing their significance.

Each abstract narrative elaborates on the first line she makes with her loaded brush. “As soon as something is visible, it becomes something to react to,” she explains. The painting that emerges is a self-contained world defined through action, the visual equivalent of a work of fiction. Smaller paintings such as "Bo" and "Lu" are as succinct as short stories, whereas larger works such as "Copia" or "Complot" have the layered quality of novels.

Like Kandinsky, Kremer finds creative potential in the interstitial space between genres. (A video work in the exhibition, titled "Zuzzy," animates a set of her drawings, superimposing footage of dancers.) Both literally and metaphorically, line is Kremer’s throughline, and also connects her work to the graphic duende of artists ranging from Henri Matisse to Ellsworth Kelly.

In "Theory and Play of the Duende," Garcia Lorca wrote that the duende “draws close to places where forms fuse in a yearning beyond visible expression.” That yearning (which Matisse called “the desire of the line”) is the origin of Kremer’s new abstract paintings. The destination is in the imagination of each viewer for whom they make meaning.

Lindsay McCrum

Male Fiction

February 20, 2025 - May 20, 2025

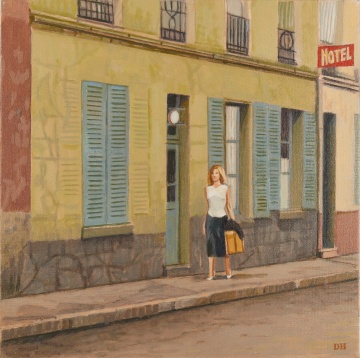

The photographs in "Male Fiction" seem vaguely familiar. The vignettes, styled and lit cinematically, appear to be part of a longer but forgotten dramatic narrative, fragments missing a beginning and an ending. Some scenes recall the suspense and ominous unpredictability in the masterpieces of Alfred Hitchcock, others the masculine libertinage in French new wave cinema. In still others, we recognize the bravado and furtive gazes of Bond-like agents and, in some, the arresting presentations in fashion advertising.

However, there is ambiguity about the images of the men themselves. While acknowledging the familiar tropes and stereotypes of stoically, inexpressive manhood, the portraits in "Male Fiction" explore the complexities beneath the surface associated with male archetypes and issues related to masculinity, sexual identity, and emotion. A complex portrayal deeply ingrained in our collective memory and popular culture.

In "Male Fiction," Lindsay McCrum creates nuanced and unexpected portraits of male beauty in contemporary settings. She uses the conventions of movie making and advertising as backdrops and vehicles for her pieces of fiction, combining lighting, costuming, staging, and camera placement to create the dramatic look of these images.

Yet McCrum doesn’t replicate actual movie scenes. Her subjects are not photographed on constructed sets but rather on location in and around Los Angeles, San Francisco, and the Bay Area. Inspired by Hitchcock, she makes strong visual use of familiar—and famous—landmarks in San Francisco: The Legion of Honor, Aquatic Park, and the Headlands.

Also, with this work, McCrum pays homage to the Eastern European graphic artists who shaped the revolutionary poster art of the French New Wave. With bold, electrifying colors and dynamic compositions, she creates a fusion of cinematic allure and graphic influences. Trained as a painter, Lindsay McCrum’s photographs incorporate principles of light, form, and gesture. But as a fine art photographer, she understands that the stories conveyed in these images lie beneath the surface. The man in the white dinner jacket, martini in hand; the man in sunglasses staring blankly out to sea; the man in the rearview mirror with his furtive gaze all embrace elements of strength, surprise, quiet dignity, love, and even arrogance. Inwardly, these heroes exhibit the emotional range of everyman. Their outward appearance is male fiction.

Lindsay McCrum’s work has been exhibited across the U.S. and Europe at museums including Museum Fur Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg, Germany; MIT Museum, Boston, MA; Palm Beach Photographic Centre Museum, Palm Beach, FL; and Ross Art Museum, Delaware, OH. There are three monographs of her work. Her books and work have been reviewed and featured in US publications and media such as TIME Magazine, The New York Times, NPR, Wired, NPR’s All Things Considered, Los Angeles Times, Juxtapoz, Today, W Magazine, and the Huffington Post. Lindsay McCrum lives and works in San Francisco and New York.

GALLERY HOURS:

MONDAY-THURSDAY 5-9:30PM

FRIDAY 5-10PM

SATURDAY 11AM-2PM & 5-10PM

SUNDAY 11AM-3PM & 5-9PM

CALL (415) 648-7600 TO CONFIRM GALLERY ACCESS

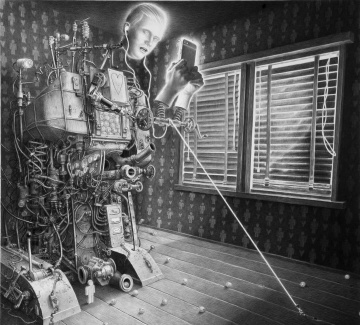

Mark Stock

Peripeteia

January 18, 2025 - March 1, 2025

Visiting the Louvre in 1993, Mark Stock was mesmerized by "The Magdalene with the Smoking Flame" (c. 1640). In subject matter, the seventeenth century religious scene was a world apart from Stock’s depictions of trysting lovers and despondent butlers. Yet the tour de force by Georges de La Tour [1593-1652] anticipated Stock’s paintings in ways that became more and more apparent the longer he gazed. In "The Magdalene" and other works Stock studied, de La Tour told a complicated story in a single frame using light as his narrator.

Returning to his Oakland studio, Stock paid tribute to de La Tour’s candles. In a series of large canvases, he painted their portraits. Positioned front and center, the candles became characters as romantic as his lovers and as forlorn as his butlers. Stock also introduced candles into his own artwork, letting them narrate the film noir plotlines that increasingly occupied his paintings.

The intense exchange between Mark Stock and Georges de La Tour is one of the pleasures of looking at Stock’s oeuvre, a vast body of work created over a four-decade career tragically abbreviated by his premature death in 2014. An incisive retrospective at Modernism shows highlights dating back to 1984, when Stock started to explore the narrative potential of contemporary figurative painting and began to develop characters including his ever-evolving butler.

At the time, Stock was living in Los Angeles, and one of his primary frames of reference was cinema. Even more than film noir, Stock drew inspiration from Charlie Chaplin, whose Tramp showed Stock how to convey his feelings through an alter ego. “When I was in turmoil and painted myself as the butler,” Stock told the writer Barnaby Conrad III in an eponymously titled monograph, “I felt I was making a painting the way Chaplin would make a film. The butler is the Tramp and the Tramp is the butler, and I’m the butler too.”

Anticipated by "The Bellhop" (1984), the butler is represented in the Modernism retrospective with "The Butler’s In Love #17" (1986) as well as three trompe l’oeil paintings from 2006. While the two paintings from the ‘80s show Stock’s talent for communicating emotion through gestures and facial expressions – showing the unrequited yearnings of servants in love with those a class above them – the 2006 series highlights Stock’s remarkable blend of technical mastery and conceptual audacity. Drawing on the 19th century still life tradition of William Harnett and John Haberle – as well as the philosophical games of literary figures including Jean Baudrillard and Jorge Luis Borges – the trompe l’oeil paintings create a metanarrative in which the butler has been sketched and the drawings kept as souvenirs. Might the drawings belong to the butler’s mistress? Might he have given them to her? Might his love have been requited after all, his mistress a mistress in both senses of the word? These Proustian possibilities and others are intentionally left open for interpretation by the viewer.

Stock saw a connection between trompe l'oeil illusionism and magic, which he performed with elan and which provided another important inspiration. The connection is explicit in "Reverie #11" (2008), which shows the legs of a performer levitating over a trompe l’oeil stage set. It’s also evident in several paintings depicting performers from Teatro Zinzanni, a San Francisco dinner theater that became a second home for the artist.

From Stock’s perspective, the theater was as imbued with theatricality off stage as much as under the spotlight. Like the film noir intrigues he evoked in paintings such as "Gnaw" and "Ponder" (2003), he created backstage tableaux that could be interpreted in myriad ways, all dramatically unresolved. Near the end of his life, he lit some of these paintings with the glow of smartphones, a postmodern update on Georges de La Tour’s candles. We will never know what is written on the phone illuminating the performer’s face in "Elena in Rapture" (2011) any more than the letters in the hands of "Candace" and "Michael" (2006). Like Stock standing in front of "The Magdalena" at the Louvre, all we can do is to continue looking in wonder.

Mark Stock’s works are in the permanent collections of institutions including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, and the Library of Congress. He is also acclaimed for his stage and costume designs, realized for the Los Angeles Chamber Ballet and the Rudy Perez Dance Company.

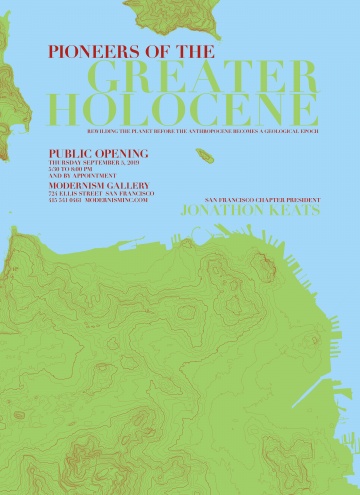

Jonathon Keats

The Future Democracies Laboratory

October 30, 2024 - October 30, 2024

THE PUBLIC IS INVITED TO THE GRAND OPENING OF THE RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT SHOWROOM ON WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 30TH FROM 6-8PM

PATENT FILED ON DEMOCRACY AHEAD OF 2024 ELECTION AS DEFENSE AGAINST FUTURE POLITICAL SHENANIGANS

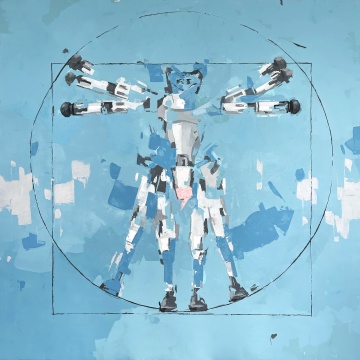

Innovations Include Legislative Automation and Nonhuman Voting System… Research and Development at San José State University’s Future Democracies Laboratory… Prototypes to be Exhibited in San Francisco Showroom on October 30th… Inventions Pledged to Political Patent Commons

Confronting simultaneous crises in American democracy and global ecology, a pioneering laboratory at San José State University has invented technologies to fundamentally alter elections and governance. Under the direction of experimental philosopher and artist Jonathon Keats, working in collaboration with SJSU faculty and students, the Future Democracies Laboratory has developed protocols for including all living beings in politics in order to better represent the interests of the whole planet. The lab has also prototyped breakthrough technologies to make laws reflecting the will of a taxonomically diverse electorate without the problematic interventions of human politicians. A newly-formed patent commons will ensure that these innovations are available to everyone.

“People constantly gripe about the partisanship and corruption of elected officials, and the inadequacy of their policies.” says Mr. Keats. “It’s hard to disagree, given the degree of discontentment with the world in which we live. Our lab is dedicated to exploring root causes of dysfunction and investigating alternatives by fearlessly asking 'what if?'”

On the eve of the 2024 election, as discontentment verges on revolution, the laboratory will open a showroom in San Francisco’s Modernism Gallery , unveiling technologies that radically rethink centuries of political dogma. “Our work originated more than a decade ago with a simple thought experiment,” Mr. Keats explains. “What if we re-engineered our political system to operate without people at the helm?” The lab replaced politicians with random number generators weighted to represent the will of the majority with high frequency but without perfect fidelity, providing a crucial check on the tyranny of the masses. These random number generators, one for each member of Congress, were configured to emulate the legislative process, with new laws generated by random mutation of legal code from the past.

Mr. Keats quickly recognized that the thresholds of random number generators could be adjusted continuously, reflecting realtime changes in political sentiment, but he also realized that people wouldn’t want to spend their whole lives inside a voting booth. “Instead of requiring citizens to register their preferences by punching holes in cardboard, I reasoned that we could simply monitor changes in their stress level,” explains Mr. Keats. “We can measure physiological changes such as heart rate, increasing the probability that random number generators will vote for change as stress increases. For even greater accuracy, biomedical devices have the potential to measure changes to the stress hormone cortisol from one moment to the next.

Humans are not the only animals to use cortisol as a stress hormone. Based on this fact, the voting system has been conceived to include input from mammals ranging from orangutans to chipmunks, as well as birds and bees. Other species manifest stress with other hormones that are no less measurable. For instance, stressed plants emit a volatile called ethylene. The Future Democracies Laboratory is collaborating with organizations including the Institute of Contemporary Art San José, the University of South Australia, and Earth Law Center to integrate all of these inputs into democratic decision-making and to inspire human voters to reconnect with the rest of nature.

“In terms of biomass, our species constitutes less than one percent of life on Earth,” says Mr. Keats, who also serves as Earth Law Center’s principal philosopher. “Humans are oblivious to most of what happens on our planet, and our human neurobiology limits our thinking. To ignore the perspectives of other species is reckless and also deeply unfair to them. Environmental justice depends on more holistic governance.”

Keats emphasizes that the lab’s stress-based voting protocol and automated congressional platform are still largely untested in the wild and may not achieve their desired goals. “They could turn out to be catastrophic,” Mr. Keats admits. “As a research laboratory, we’re investigating possible futures to assess how they might impact society before they’re enacted. We’ve preemptively filed for patent protection – and secured a provisional patent – in order to prevent corporate and political opportunists from profiteering.

“Equally important, by presenting our speculative technologies to the public and allowing people to interact with them in our San Francisco showroom, we’re engaging the community in the process of deciding collectively what’s in our best interest: democratizing how we conceptualize democracy.”

On October 30th, from 6:00 to 8:00 PM, a selection of technologies will be on view in the Future Democracies Laboratory’s San Francisco showroom at Modernism Gallery , where they’ll be shared with the public and made available for licensing by companies seeking innovation in corporate governance. Apparatus on view will include a legislative mutation board and an experimental voting system for houseplants.

Concurrently, the Institute of Contemporary Art San José will showcase a range of Future Democracies Laboratory prototypes including an interactive electronic apparatus for reconfiguring government developed at SJSU’s CADRE Laboratory for New Media in collaboration with Professor Steve Durie. The apparatus will be installed at the ICA until February. Collected data will inform future R&D.

About Jonathon Keats

Acclaimed as a “poet of ideas” by The New Yorker and a “multimedia philosopher-prophet” by The Atlantic, Jonathon Keats is an artist, writer and experimental philosopher whose conceptually-driven transdisciplinary projects explore all aspects of society, adapting methods from the sciences and the humanities. Keats is currently a fellow at the Berggruen Institute, a research associate at the University of Arizona, a research fellow at the Highland Institute and the Long Now Foundation, principal philosopher at Earth Law Center, an advisor in metadisciplinary studies at the University of Zürich, and an artist-in-residence at the SETI Institute and Flux Projects. A monograph about his work, Thought Experiments, was recently published by Hirmer Verlag.

45th Anniversary Exhibition: Part II

September 26, 2024 - December 21, 2024

In the early 1980s, the art world didn’t know what to make of Andy Warhol. Already famous for silkscreening all-American icons such as Marilyn Monroe, Warhol had begun to represent more problematic iconography with equally deadpan irony. Most troubling of all was the hammer and sickle—a symbol of the Soviet Union—which had become an emblem of Communist aggression and Cold War tension. Warhol astutely recognized that the hammer and sickle had fallen into the same category as Marilyn, turned into kitsch by endless replication.

Warhol’s articulation of this equivalence was bound to resonate with Martin Muller, an art dealer who had recently made his name with the first show of Russian and Ukrainian avant-garde paintings in San Francisco. Muller had seen the Soviet propaganda machine from the inside. Visiting the Factory one afternoon in 1982, Muller offered Warhol a solo show at Modernism.

Warhol’s first-ever gallery appearance in Northern California, the Modernism exhibition drew a crowd. Hundreds of people attended the opening. A month later, it was still the talk of the town. Muller had guaranteed to sell two of Warhol’s paintings, priced at a bargain $25,000 apiece. He’d sold only one and had to buy the second work for himself.

Forty-two years later, as the gallery celebrates its 45th anniversary, nobody has any doubts about Warhol’s importance or Muller’s prescience. From the Russian and Ukrainian avant-gardes to Pop; Photorealism to socio-political art, etc., Modernism has consistently exhibited work that less adventurous galleries have shunned, only to show time and again that artistic quality is more important than popular taste.

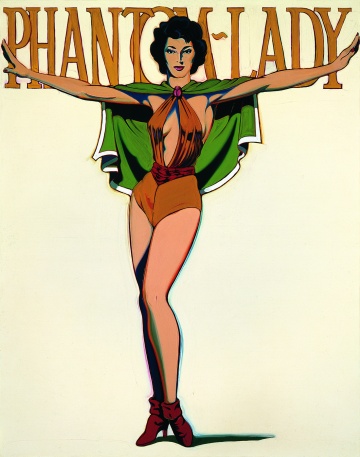

Part I of the 45th anniversary show featured the Russian and Ukrainian avant-gardes as well as several other areas of concentration such as Nouveau Réalisme and hard-edge abstraction. Opening on September 26th, Part II will largely complete the picture. Alongside one of Warhol’s hammer-and-sickle paint drawings, the new exhibit features work by a couple other seminal Pop artists who once struggled only to triumph. Mel Ramos, who independently started to work with superheroes at the same time as Roy Lichtenstein and Warhol, is represented by two 1960s works: a painting depicting the Phantom Lady and a drawing of Superman. Ed Ruscha, currently the subject of a major career retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, is represented by "So," one of his signature word paintings. For all the manifest differences between Soviet propaganda, American superheroes, and glib turns of phrase, these three works show how Pop art has uniquely foregrounded images and language so familiar as to be practically imperceptible. The artwork awakens the viewer to the sociocultural operating system of contemporary society.

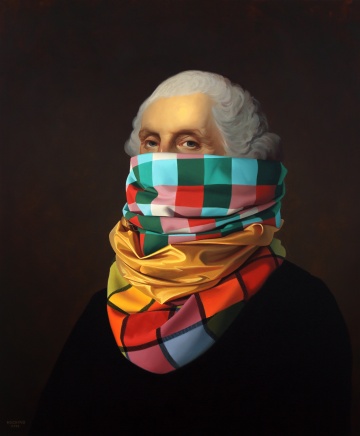

Pop strategies and aesthetics have taken different directions in the hands of younger generations, and Modernism has been attentive to these important developments. Since the 1980s, Jerry Kearns has given Pop iconography a decidedly political turn, often through his deft juxtaposition of imagery that society compartmentalizes, turning a blind eye to the relationship between categories such as consumer culture and warfare. "Hearts & Minds," for instance, juxtaposes a ‘60s-era comic strip kissing scene with the famous Vietnam War photograph documenting a nine-year-old girl running naked through the street following an American napalm bombing. Even more recently, Shawn Huckins has appropriated work of famous painters such as John Singleton Copley’s 1782 "Midshipman Augustus Brine," irreverently cloaking the fashionable subject in outrageously colorful yarn. Woven using a latch hook technique learned from Huckins’ grandmother, the textile tweaks the masculine posturing of the future British admiral.

Peter Sarkisian is another Modernism artist who utilizes mixed media to upset expectations. His "Ink Blot" is an animation in which a man emerges from a spilled bottle of ink and crawls to a sheet of paper on which he makes his mark, only to fade away. This neo-Surrealist work is featured in a video room that also includes mixed media video works by Naomie Kremer (who projects a moving female figure on one of her figural abstractions such that the brushwork comes to life), and Jonathon Keats (who has concocted a TV dinner for plants by immersing them in the colored light of a television for their photosynthetic delectation). Set in dreamy darkness, all of these works evoke alternative realities.

Photography is another highlight of the exhibition, including one of Judy Dater’s most iconic images, a 1974 portrait of an elderly Imogen Cunningham happening upon a nude female model, Twinka Thiebaud, in Yosemite. By evoking and challenging historical works such as Thomas Hart Benton’s "Persephone," Dater’s double portrait makes a decidedly feminist statement on the history of art. Also of note is a 1939 vintage print of Lisa Fonssagrives vertiginously posed atop the Eiffel Tower by the great Dadaist and later, midcentury fashion photographer Erwin Blumenfeld.

When he first moved to Paris in the ‘30s, before he made his name shooting fashion for "Vogue," Blumenfeld created a series of portraits of important French artists including Henri Matisse, who he subsequently befriended. The influence of Matisse on the younger artist is evident in Blumenfeld’s treatment of flesh and garments in both the fashion photography and his many artistic nudes. So, it’s apt that the Modernism exhibition also includes one of Matisse’s odalisques, previously shown in the gallery’s retrospective of Matisse’s prints.

Beyond the U.S., Asia, the Middle East and the USSR, Muller has focused on Francophone Europe, including France and Switzerland. Of particular note in the 45th anniversary show are important Cubist works by Henri Hayden, Albert Gleizes, and Georges Valmier. (Created in 1919, Hayden’s still life painting reveals how deeply his work was in dialogue with contemporaries including Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Juan Gris.)

Nearly two decades before the 2022 Matisse exhibition, Modernism hosted the first monographic exhibition in the United States devoted to works by the great Swiss architect Charles-Edouard Jeanneret. Better known as Le Corbusier, Jeanneret introduced Modernist principles to housing and whole cities. His artistic practice was underappreciated throughout the 20th century. Many connoisseurs of his contributions to urbanism dismissed his drawings and collages and gouache paintings as diversions. Le Corbusier knew better, writing that he had “found the intellectual seed of my urbanism and my architecture” within his purely artistic practice. The exhibition at Modernism helped to buttress this claim, and also to reveal some of the visual foundations of his lyricism.

Like Andy Warhol and many other artists featured in Modernism’s more than five hundred exhibitions, Le Corbusier is seen today in a way that Muller anticipated. On a daily basis, Modernism functions as a gallery, but the long-term vision and supporting scholarship give the gallery the artistic heft of a museum.

Victor Reyes

Memory Only

September 19, 2024 - January 10, 2025

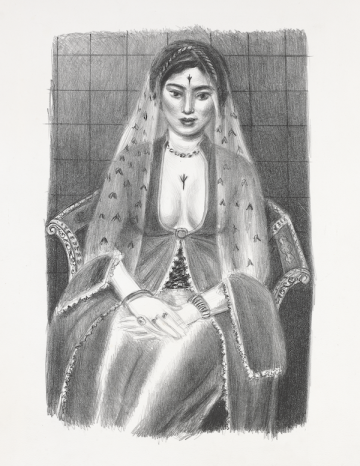

Victor Reyes (b. 1978) arrived in San Francisco by way of Los Angeles in 1998. The City, bursting with the potential of its first tech boom, teetering precariously on the turn of a new millennium, and anxious with preoccupations of the Y2K scare, served as a muse and a teacher to Reyes. With changes coming in waves, ripping with the currents of a “mobbing culture heading towards the future” Reyes recounts the experience of watching a “higher consciousness forming.”

Already a Southern California street art icon, Reyes established himself in the Bay Area with an expansive public art project, painting murals of each letter of the alphabet around the city’s Mission District. Doing so, Reyes gladly obscured his role as a formal or informal artist.

Modernism is pleased to present its first solo exhibition of sixteen paintings and works on paper by Victor Reyes. "Memory Only" is on view from September 19, 2024 to January 10, 2025.

The exhibition title reflects the ephemerality of the chimera Reyes once observed, a time and place that exists now only as memory. He recalls watching “the cellular death of the twentieth century” as the digital age was ushered in. This convergence is echoed in the competing presence of the gestural marks, Matisse-like organic forms, and hardedge techniques found in this group of paintings, all created by painting a series of opaque and translucent layers with the use of screens and molds. With a color palette that ranges from bright and lively to dark and muddled, the works in "Memory Only" hold vigil for the vestige of San Francisco.

Victor Reyes has shown extensively around the world, in Bosnia, Germany, Switzerland, Taipei, Japan, and the United States. Reyes is an internationally recognized street artist and has worked with notable brands such as Louis Vuitton, Facebook, Twitter, and Nike. He now divides his time between San Francisco and Detroit.

THE PUBLIC IS INVITED TO A RECEPTION FOR THE ARTIST ON THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 19TH FROM 6-8PM AT MODERNISM WEST

MODERNISM WEST / FOREIGN CINEMA

2534 MISSION STREET

SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94110

GALLERY HOURS: MONDAY-SATURDAY 5-10PM, SATURDAY 11AM-2PM, & SUNDAY 11AM-3PM

CALL (415) 648-7600 TO CONFIRM GALLERY ACCESS

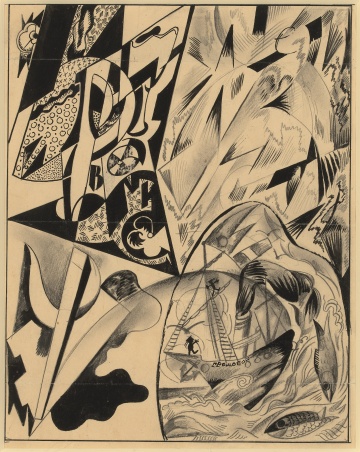

45th Anniversary Exhibition: Part I

July 5, 2024 - August 30, 2024

In the Spring of 1980, six years before Mikhail Gorbachev introduced “glasnost” to the Soviet Union, Modernism gallery brought Russian avant-garde art to the West Coast of the United States. Barely six months old and situated in a large, minimalist-designed, second-floor space in San Francisco’s then edgy South of Market district, Modernism defied censorship in the USSR and provincialism in San Francisco with a museum-quality exhibition that included works by Kazimir Malevich, Liubov Popova, Alexander Bogomazov and a dozen other seminal artists working in the teens and twenties.

The historical exhibition provided crucial context for the gallery’s presentation of contemporary abstract artists including David Simpson, Frederick Hammersley and James Hayward, whose paintings reciprocally enriched the rarely seen work of the Soviet artists who pioneered abstraction in the heady decades ahead of Stalinist oppression. In the fledgling SOMA district gallery, past, present and future formed a creative continuum.

Forty-five years later, resituated in a bespoke street-level space in San Francisco’s Tenderloin, Modernism continues to bring art of historical importance into dialogue with the most recent advances worldwide. Gallery founder/owner Martin Muller has expanded the program to include virtually every significant 20th and 21st century movement, from Dada, Cubism, Surrealism, Vorticism and German Expressionism to Pop, Formal Abstraction, Photorealism and Conceptualism.

In celebration of the 45th anniversary, Modernism is pleased to present a two-part retrospective showcasing dozens of the artists whose work has defined the gallery, enhanced cultural life in the city and contributed to art history. Opening on July 5, Part I will be on view until August 31. Part II is scheduled to open in September.

The Russian avant-garde, which Modernism has presented in twenty historical exhibitions over the past forty-five years—including masterpieces such as Kazimir Malevich’s 1917-18 canvas “Supremus No. 84” —is represented in Part I with work by many of the artists featured in 1980. Highlights include Malevich’s important study for “Samovar II” (1913), a multifaceted Cubo-Futurist painting shown in his 1919 retrospective and currently in MoMA’s permanent collection. Also noteworthy is Popova’s oil-pastel study for “Spatio-Dynamic Construction” (1921), a “tour-de-force” of pure abstraction in which the artist audaciously set geometry in motion. A third work of particular significance is “Man Walking Into Cubo-Futurist Landscape,” a 1914 charcoal drawing by Bogomazov that boldly walks the line between figuration and abstraction, questioning where one ends and the other begins. (A Ukrainian artist from Kyiv, Bogomazov received his first US retrospective at Modernism in 1983.)

Contemporary abstraction is also strongly represented in Part I of the retrospective, with hard-edge works by Hammersley and Simpson, and two of Hayward’s signature Formal Abstract monochrome paintings, one flat and one thickly impastoed. Also of note is Edith Baumann, whose acrylics appear to float, as ethereal as pure thought. At the opposite extreme is Hermann Nitsch, whose violent “Schuttbild” (1986) takes inspiration from Aktionist performance works involving spilt blood; Arnulf Rainer, whose electrifying “Alexandre” (1991) deconstructs a historic engraving with an overlay of pencilwork and paint; and Jacques Villeglé, whose visceral “FFF” (1997) was achieved by peeling away layers of advertising from a billboard found in Agen, France.

Photography has been another essential aspect of the Modernism program since the 1980s, and is represented in Part I with work by masters such as Man Ray and Lucien Clergue, shown together with conceptually-driven contemporary artists such as Elena Dorfman and Alex Nichols.