Krakow Witkin Gallery

10 Newbury Street

Boston, MA 02116

617 262 4490

Boston, MA 02116

617 262 4490

Krakow Witkin Gallery features contemporary art of all media by emerging and established regional, national and international artists. The overall focus is on Minimal, reductivist and conceptually-driven works.

Artists Represented:

Robert Barry

Mel Bochner

Robert Cottingham

Tara Donovan

Peter Downsbrough

Mike Glier

Jenny Holzer

Bronlyn Jones

Alex Katz

Ellsworth Kelly

Estate of Sol LeWitt

Allan McCollum

Julian Opie

Liliana Porter

Stephen Prina

Kay Rosen

Ed Ruscha

Estate of Fred Sandback

Richard Serra

Kate Shepherd

Kiki Smith

Shellburne Thurber

Ursula von Rydingsvard

Works Available By:

Josef Albers

Richard Artschwager

John Baldessari

Bernd + Hilla Becher

Daniel Buren

Dan Flavin

Philip Guston

Jenny Holzer

Donald Judd

William Kentridge

Robert Mangold

Brice Marden

Michael Mazur

Abelardo Morell

Robert Moskowitz

Bruce Nauman

Claes Oldenburg

Julian Opie

Sylvia Plimack Mangold

Robert Ryman

Richard Serra

Kiki Smith

Sarah Sze

Lawrence Weiner

“On Kawara"

“Echoing” Featuring works by Philip Guston, Sol LeWitt, Julian Opie and Liliana Porter.

“Julian Opie”

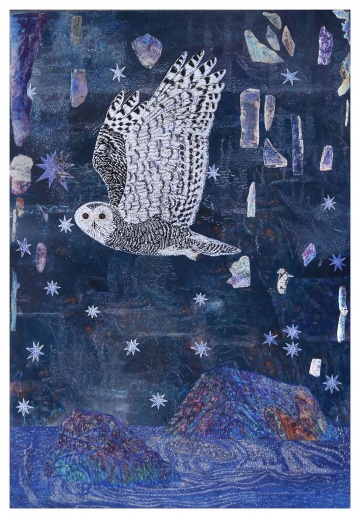

"Kiki Smith: Frequency"

“Relatives” Featuring works by Mike Bidlo, Liliana Porter, Jonathan Seliger and Haim Steinbach

"Fred Sandback Editioned Sculptures and Related Works on Paper"

"Gacing Grain" Featuring works by Sylvia Plimack Mangold Frank Poor Analia Saban.

"Richard Serra: 1985-1996"

Julie Mehretu, Sarah Sze, Jacques Villon

Julie Mehretu, Sarah Sze, and Jacques Villon

January 17, 2026 - March 7, 2026

Krakow Witkin Gallery presents an exhibition of works by Julie Mehretu, Sarah Sze, and Jacques Villon. Mehretu and Sze both have active studio practices today, while Villon passed away in 1963. Perhaps an unexpected grouping, the exhibition departs from a thematic or stylistic framework to instead offer viewers the opportunity to engage deeply with three approaches to image-making, mark-making, and composition. Rather than shared history, what brings these pieces into dialogue is each artist’s individual methodology for mapping out and constructing visual space.

“Achille (epoch)” by Julie Mehretu (b. 1970, Ethiopia) is a nine-color etching with aquatint and spitbite, created in 2015. The title and the medium of this work both point toward the artist’s multi-layered practice. While Mehretu frequently works from photographic source material and uses titles that suggest a situation or narrative, the artist's imagery is inherently abstract.

In the exhibited work, each layer of printing suggests successive fields of marks, with highly differentiated line qualities, colors, and energies. The marks themselves are the visible actors of the print, yet their relationships map out interstitial spaces that suggest a living, shifting visual landscape where depth seems to exist and yet no definition of that space can be discerned.

Sarah Sze (b. 1969, Boston) has cultivated a practice that incorporates found objects which have, in her words, “little individual identity” into fragmented, distributed networks of relationships and interconnections, often in the form of immersive, kinetic installations. The exhibited piece, “The Moon is distant from the Sea” (2024), embodies a microcosm of Sze’s approach in tracing a connecting line across material and pictorial space.

A white piece of string, attached to and touching the top edge of the paper, descends across the surface of the work, crossing the embossed platemark onto the digital/photographic background element. The string proceeds to descend toward the bottom of the paper. Beginning about a third of the way down, the string seems to have not only a physical shadow, but a digital shadow that originates as part of the background imagery. The string is held in tension by scraps of tape but also interrupted and redirected in places by loops and knots. The direction, orientation, and relationships of planes and objects are intentionally ambiguous, as the viewer can see the string pass both over and under the tape. This blurry field appears to mirror or continue the network of objects on the surface of the paper on and out of view, crossing a secondary picture plane that is internal to the work.

Apart from the string and tape, the only sharply defined element is a torn piece of paper, collaged to the surface, that is printed with an image of a light source in a blue sky. This too is blurry and undefined, except for an optical artifact of lens flare that brings the viewing surface back into focus. The narrative situation of the work is left deliberately undermined, while the title and the journey of the string point the viewer away from distinct, independent objects and toward a web of mutual reflections and interbeing, all of which is consistent with the artist’s continual use and reuse of imagery of her own situations within those situations. Connection, continuity, and delicate balances are key in Sze’s work.

Jacques Villon (1875 Damville, France–1963 Puteaux, France) began his career as commercial illustrator before devoting himself to painting in 1910, around the same time that he established the Puteaux group, a Cubist collective that included Robert Delaunay, Fernand Léger, Francis Picabia, and Villon’s brother Marcel Duchamp, among others. The tension between representation and pictorial abstraction would continue to be an activating force in Villon’s work throughout his career.

A consummately skilled draughtsman and printmaker, Villon tirelessly studied and experimented with the construction of image space through the articulation of marks. He developed many works through multiple studies and versions that show the outer forms emerging in layers like geological strata. The exhibited engraving, “Quartier de bœuf” (1941), is an image that has been painstakingly built up through hatching in successive passes and directions, where a full range of tonal values has defined the volumetric space of the eponymous side of beef, but the artist has stopped just short of adding surface detail to clearly denote the subject.

Like the display of butchered meat, Villon has printed his engraving plate with all raw lines fully exposed in their fragility. The ambiguous form has an elegant and yet raw corporality. In some places it suggests a torso, recalling the wartime period in which it was printed. The tones are heavy and solid, while the visible fabric of the linework denotes an incomplete state of becoming and undoing. While unusual to place Villon’s work in this context, the hope is for a renewed interest and exploration into the artist’s devoted, fluid, and yet raw approach to artmaking.

Joseph Grigely

One Wall, One Work: Joseph Grigely

January 17, 2026 - March 7, 2026

Joseph Grigely (b. 1956) was born and raised in East Longmeadow, Massachusetts. At the age of ten he fell down a hill and became completely deaf. At this point, he began a journey that he describes as “watching the world with the sound turned off,” paying close attention to language, communication, and the vagaries of human interaction. Grigely is an artist and writer whose work addresses questions about the materialization of language and communication, and the ways conversations might be represented in the absence of speech.

The work currently on view, “Paula's Birthday Party,” literally does what conversations around a table typically do: it turns. From one speaker on one side to another speaker on another side, and sometimes both speakers talking on top of each other. It illustrates how conversations are fragmented, layered, and how there's no fixed trajectory between the beginning and the end.

The imagery comes from a conversation—on a tablecloth, from a restaurant on Spring Street in New York City in 1996, during a birthday party for the artist Paula Hayes. Over the years, Grigely kept the cloth, but the original inks had faded, and the wine spills oxidized from red to brown. In 2016, the availability of high-resolution scanners for oversized documents meant that the tablecloth could be scanned. Through careful editing of the colors and contrast of individual lines, the work was brought back to life, and the various aspects and layers (different inks, stains, etc.) were unified as an archival pigment-based print. Furthermore, the work is hung diagonally, so that the viewer is positioned as the artist was: between two people, one on the right and one on the left. This format is also intended as a formal reference to Mondrian's diagonal paintings.

In 2026, Joseph Grigely will have solo exhibitions at Palais de Tokyo, Paris, and Air de Paris, Paris, and will be included in group exhibitions at Syracuse University Art Museum and Musée d’art contemporain de Marseille. A new publication will be released by Palais de Tokyo. In 2025, he had a solo show at The Shed, Rouen, France, was included in group exhibitions at Z33, Hasselt, Belgium, Museum Voorlinden, Wassenaar, Holland, Maxxi, Rome, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, La Chartreuse, Avignon, Foundation Vincent Van Gogh, Arles, and Robert Heald Gallery, Wellington, New Zealand. In addition, he was the subject of two interviews, one with Ayden LeRoux in the Winter 2026 issue of Bomb magazine and one with Rachel Be-Yun Wang in Documenting Time Countering Form (London: Chisenhale Gallery). His latest book, Otherhow: Essays and Documents on Art and Disability, 1985-2024 was released in January 2026 by Primary Information.

Sylvia Plimack Mangold

Sylvia Plimack Mangold: Tape, 1975–1986

January 17, 2026 - March 7, 2026

My work is not about fooling the eye but about questioning the nature of painting and thereby the nature of levels of reality. The only element which is true to itself is the paint when it is applied as a covering on a flat field. You see this painting; it looks incomplete. I have deliberately painted that state of incompletion, so that it is finished. I am interested in my own evaluation of finality. Finality or finished is an idea, a question which seems to continue, a point when the elements have a lively relationship. Presently, a primary issue for me is the dichotomy between spontaneity and calculation. The work should appear free, when in fact in order to recap that quality there is a very complex process I must sustain. It is further complicated by making the process the content.

—Sylvia Plimack Mangold

Krakow Witkin Gallery presents an exhibition of Sylvia Plimack Mangold’s works made between 1975 and 1986 that incorporate imagery of tape. From paintings of the depiction of bits of tape “adhering” imagery of paper to the surface of real paper or canvas, to the representation of tape as a cropping and/or masking tool, the current show gives viewers a deep look into how the artist progressed in her thinking and execution over the course of a decade.

For works made prior to those on view, the artist often employed adhesive masking tape as a technical tool in her work. As she spent more time with the material, she appreciated and focused on certain of tape’s physical and psychological qualities including its translucency that selectively obscures and transforms underlying forms and colors, its role as a connector between surfaces and objects, and its ability to frame and draw attention to both a picture plane and its boundaries. This interest led Plimack Mangold to pursue incorporating tape into her finished pieces by creating imagery of masking tape within her works.

She painted, drew, and printed what appears as a painter’s traditional use of tape, to temporarily mask an edge in the process of making an image. In addition, Plimack Mangold explored how, while the imagery of tape being used for cropping an image gives a central focus, the tape itself was of interest. This highlighted the process of how an artist decides how and what to include and, in emphasizing the edge, subtly undermined the center-weighted focus of representational art.

In all of this, she used actual tape to aid in the creation of imagery of tape, by masking off areas to make sharp-edged, thicker layers of paint to simulate the material itself. Even while using this technique, she never gave in fully to verisimilitude. The means of making the image remain in constant tension with the result.

Recognizing that tape, like floors she had painted in the 1960s and early 1970s, was part of the human, domestic world, the artist sought to introduce a contrast and an expansion of space. By the late 1970s, Plimack Mangold’s work frequently includes imagery of nature. Her explorations began with views through her studio window. The window soon no longer appeared in the work as the tape, itself, became the frame. From then on, she painted what she saw outside her studio: beginning with skies containing slow transitions of color from the horizon upwards; clouds; long vistas with barely discernible mountains and valleys; scenes in a nearby field; shifting ultimately to a focus on trees and their limbs. With all these images, tape was a constant, reminding a viewer of the deliberate and fabricated nature of a scene.

Sylvia Plimack Mangold’s works from 1975 to 1986, as exhibited in this show, display the psychological charge of the exchange between artist and viewer, human and nature, image and object, and process and result. As such, they are deliberately open-ended, experiential, and self-reflective, offering the viewer a journey of layered examination to mirror and continue the artist’s practice.

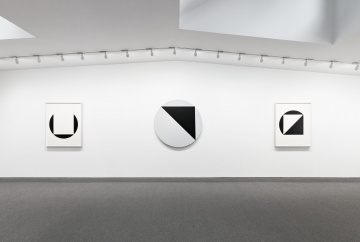

Leon Polk Smith: Circle and Square, 1948–1987

September 13, 2025 - October 18, 2025

“What I was seeking through the 1940s was to find my outlet from this vertical/horizontal and to express the same thing that Mondrian had worked with, that is the form-space equilibrium, the interchangeability of form and space. I wanted to find a way of using that in a curvilinear manner, in curved lines, free forms. It looks so very simple. I always thought it looked as if an idiot could have done it overnight. But I was seven or eight years finding that.”

–Leon Polk Smith

Krakow Witkin Gallery has presented the work of Leon Polk Smith (1906–1996) in several contexts over the past thirty years, but the current show is his first solo exhibition at the gallery. In addition, it is the first presentation of his work to place his editioned prints in the context of his paintings, drawings, and collages.

Smith was born in Oklahoma territory to undocumented Cherokee immigrant parents from Tennessee. He grew up in impoverished circumstances surrounded by Chickasaw community culture. He initially worked on his family farm and then as a journeyman laborer to help support his family. Filled with academic drive, he attended college In Oklahoma and went on to study at Teachers College at Columbia University in New York City. All the while making his own art, he supported himself teaching and as education administrator in Delaware, Georgia, and Florida, before finding his way back to New York City. In 1941, Smith had his first solo show in Manhattan.

Over the next six decades, culminating with his 1995–96 retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum, Smith sustained a solid, growing reputation as an early and continuing innovator in reductive geometric abstraction and complex, multi-part shaped canvases. In the 1950s and ’60s, younger painters including Al Held, Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, and Jack Youngerman visited his studio, placing his work at a key moment in the transition from gestural to hard-edge abstraction.

Having first internalized the forms, meanings, and aesthetics of Oklahoma Native American art and culture, Smith, like other US abstract artists, was deeply influenced by the art of Picasso, Mondrian, Arp, Brancusi, and Matisse. He explored other cultural approaches to image, shape, and color in a way that was referential, personal, and yet generalized enough to be broadly accessible. The current show is a survey from 1948 to 1987 of Smith’s exploration of circles, squares, and triangles, along with their interrelationships in positive and negative space. While some works in the show emerge from a single type of shape, most works display the artist's masterful use of tension between shapes that he developed over a lifetime of dedicated investigation.

In February 2026, the Addison Gallery of American Art will open “Both Sides of the Line: Carmen Herrera & Leon Polk Smith,” organized by the University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor, where it is presently on view. The exhibition is accompanied by a major publication.

Krakow Witkin Gallery thanks John Koegel, Patterson Sims, and Ginger Miller of the Leon Polk Smith Foundation, as well as Betsy Senior Fine Art, for making the current exhibition possible.

“I think that the proportion of the canvas comes first. I have a feeling that I want to do a canvas about a certain size, and I don’t know just what I am going to paint so I stretch it to size and hang it on the wall and sit down and look at it. Sometimes I figure: Oh, should I do anything to it? A well stretched canvas is very beautiful, just to sit and contemplate. And then the proportion, the size of the canvas often suggests a form. I will get up and draw this one line through the canvas which creates two forms, one on either side of the line, and while I am drawing this line, it seems that I am traveling many, many miles in space instead of just fifty inches or sixty inches whatever the canvas happens to be, but it is a great, great distance from one point to the next and around the curve, and I begin to feel the tensions develop and the forces working on either side of this line.”

–Leon Polk Smith

William Kentridge

One Wall, One Work

September 13, 2025 - October 18, 2025

"What we take as a finished fact, this image of a landscape, of a garden, as we see it here, in fact is always a willful construction, not of rational thinking, but of this element of us that needs to try to make sense of the world ... And what that suggests is that the way of apprehending the world, we all have to do, making sense of fragments, saying we understand history and what we do is we take different fragmentary stories and pieces of facts and dates and construct a possible history."

–William Kentridge

For artist William Kentridge, mishearing is a key creative and philosophical principle, representing the way the human mind constructs meaning from uncertainty. In Kentridge’s practice, misunderstanding and mistranslation are not failures, but fruitful moments that generate new ideas and narratives. In an often-told story, Kentridge, as a child, misunderstood about his father's work as a defense attorney for Nelson Mandela in the South African Treason Trial (1956–1961). Kentridge misheard it as "trees and tiles" due to a mosaic-tiled table and the fir trees at his family home. This memory became a powerful metaphor for understanding the world through fragments and pieces, connecting the private experience of childhood to the public sphere of political events.

In Kentridge's distinctive tree and garden works, individual sheets of paper are assembled like tiles to form the overall images, often incorporating fragmented texts. The scenes represent not just the nature depicted, but also the complexities of knowledge and history, as well as concepts of growth, decay, and interconnectedness. The spaces depicted also serve as a canvas for fragmented texts, drawn from literature and poetry, further reinforcing the idea of a multi-faceted understanding of history, memory, and the world at large.

The work currently on view at Krakow Witkin Gallery, “How to Explain Who I Was,” is the latest of the artist's large-scale works to challenge notions of veracity, completeness, and comprehension. By employing numerous different methods of reproduction (photography, photogravure, photopolymer, and drypoint etching) onto 52 sheets of seven different types of paper collaged and pinned together, Kentridge has created a scenario where various types of distinct marks, imagery, size, image source, and paper are considered equally. Photos of pins holding a piece of paper in the studio have the same relevance as actual pins holding the exhibited piece together. A photogravure of a photograph of a charcoal and India ink drawing is overlayed with direct drypoint marks. Like in much of Kentridge's work, “reality” is subjective, incomplete, reformulated, and expanded in poetic ways where parts, parts left out, and the sum of the parts are equally significant.

"It shows that the uncertainty and the doubt that is central to the studio practices are also ways of understanding the limitations of our understanding of the world and our certainties about the world, and makes a long-term argument for doubt, for being careful about being too certain on any judgments and understanding that all of these understandings of all of our understanding of different parts of the world are constructions that we make from incomplete fragments.”

–William Kentridge

Liliana Porter and Douglas Huebler

September 13, 2025 - October 18, 2025

The current exhibition features works by Douglas Huebler and Liliana Porter. Both artists use reduced visual means to explore ideas of assumption, connection, extrapolation, and imagination, and, for each artist, humor plays a key role in beckoning viewers to explore, participate, question, and wander.

Douglas Huebler (b. 1924, Ann Arbor, Michigan; d. 1997, Truro, Massachusetts) came to prominence in the late 1960s and early 1970s for making visual work that combined photographs, drawings, and/or maps along with written texts (as captions or descriptions of a process, structure, or system that relate to the imagery). Huebler created visual experiences that ask a viewer to question, doubt, and perhaps explore trust.

As an example, a 1968 piece in the current exhibition displays a grid of 24 lines that are seemingly identical. However, Huebler's caption/title reads, "24 LINES 5 1/2” LONG POSITIONED AT AN ANGLE OF 5º TO THE PICTURE PLANE (EACH LINE TOUCHES THE PICTURE PLANE AT THE BOTTOM POINT).” With a bit of thinking, a viewer recognizes that the lines are actually far shorter than 5” long but without the text, a viewer would have no way of knowing that Huebler has used foreshortening. Even with the text as explanation, one most likely still wonders whether the text is accurate. With no way to prove or disprove, the piece engages a viewer in questioning representation, subjectivity, and factuality. While made around 50 years ago, the works presciently speak to the current problematics of large language models and AI.

As a slightly later example, “Variable Piece #112 London”(1974) presents ten photographs, in five pairs denoted with letter-matching stickers. One of each pair is a photograph of a mannequin; the second is of an actual person. The connection perhaps could be guessed, but to a casual viewer it is unknown. The accompanying text states:

During a ten minute period of time a number of mannequins were photographed through the windows of clothing stores on Oxford Street. The artist allowed no more than ten seconds to pass before making a photograph of a passerby whom he felt, more than any other seen during that time, most closely resembled the mannequin thereby juxtaposing one mode of reality with another. Ten photographs join with this statement to constitute the form of this piece.

As in the previously mentioned work, a viewer can take a leap of faith and begin to see what Huebler guides one to do, or one can doubt. The choice is, of course, open but by trusting the text, a viewer can see through another’s impressions. Huebler has created balance in the work between the photographer’s perception as he responds to the constraints laid out for the work and the opportunity for a viewer to “make the leap” to “understand” how the artist saw the connections. Openness and direction are equally important in the act of exploration for the artist and the viewer.

Liliana Porter (b. 1941, Buenos Aires, Argentina, lives in New York City and Rhinebeck, New York), like Huebler, came to prominence in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Initially known for her activities with the New York Graphic Workshop, Porter made work that balanced between the use of trompe-l’oeil and empty visual space so as to allow a viewer’s imagination to complete an image. Using actual and painted shadows, physical scratches made by images of nails, and images of wrinkles on flat and on wrinkled paper provided the artist with a wealth of opportunities to confuse and delight a viewer. Over time, Porter’s imagery became less dry and her use of quotations from the realm of commercial production (postcards, well-used toys, etc.) increased. Playfulness took center stage and more emotional room became available for the audience to imagine a fuller narrative.

In the currently exhibited “To Go Back, Woman in White” (2019) Porter presents a small found figurine standing on what appears to be a simple winding path (what is actually just two parallel lines) that ends at the base of a mug, upon which she has drawn a continuation of the lines and has them end at the image of the door of a small house on the mug. All of this is sitting upon a small shelf with a softly-curving, irregular front edge. Who is the figure? What do they feel? What is the path like? Does the figure want to go home? Is the house home? All of these questions (and more) are both asked and oftentimes answered by a viewer. At this point, it’s important to pause and recognize that the viewer is asking these questions of a figurine on a spare shelf where it shares space with a mug. Self-awareness, along with empathy and imagination seem to be key for Porter as an artist. The work she makes provides a platform for viewers to appreciate those emotional and mental states all while plainly showing the homeliness of her materials and the importance of openness.

“Weaver with Black Hair” (2021) positions the small found figurine right at the edge of the work’s boundaries, her legs swinging over the lip of a long shelf. Here Porter takes a woman in put-together, yet anonymous attire and with the addition of two sewing needles, engages her in an ongoing process with the heap of textile material piled to her side and spilling off the shelf. The frozen tableau offers the viewer entry to many narratives, depending on their interpretation of who the figure might be and what she is making (or undoing). A neat storyline is not the artist’s concern here; her role begins and end with sketching the relationships between the elements of the work and the viewer. As in the other exhibited works, Porter’s engagement with still objects on the smallest scale opens up a vast horizon of possibilities over undefined time.

Carl Andre, Richard Artschwager, Daniel Buren, Chuck Close, Barry Le Va, Sol LeWitt, Agnes Martin, Robert Mangold, Sylvia Plimack Mangold, Don Nice, Myron Stout, Tom Wesselmann, and Joe Zucker

Rubber Stamp Portfolio

June 21, 2025 - July 18, 2025

50 years ago, Robert Feldman and his publishing imprint Parasol Press embarked on a project with the aim of creating something akin to a “print of the month” club. While this idea seemingly would cater to mass appeal, Parasol Press had become known in the previous five years for being among the most adventuresome print publishers, producing works with Mel Bochner, Sol LeWitt, Brice Marden, Agnes Martin, Dorothea Rockburne, and numerous others. In the end, subscribers received all thirteen prints together, not in installments, and the Rubber Stamp Portfolio, as it has become known, offered a snapshot of the New York-centered avant-garde at that moment in time.

Under Feldman, Parasol, with the project managed by Carol Androccio (later Carol LeWitt), worked with thirteen different artists to create works, each of which would be a custom-engraved rubber stamp to be inked and printed on paper as an original, limited-edition artist print. Each work was done in an edition of 1000, with each artist approaching the project with their own vision. Ultimately, several deviated dramatically from the single stamp principle, yet each in ways that reflected the exigencies of their practices. Feldman’s idea intrigued the Museum of Modern Art and their publications department so greatly that the museum requested to be, for a period of one year, the exclusive distributor for the portfolio.

The thirteen artists, whose participation mostly stemmed from Feldman’s early relationships to the Bykert and Allan Stone galleries, expanded beyond any particular boundaries, to include:

Carl Andre

Richard Artschwager

Daniel Buren

Chuck Close

Barry Le Va

Sol LeWitt

Agnes Martin

Robert Mangold

Don Nice

Sylvia Plimack Mangold

Myron Stout

Tom Wesselmann

Joe Zucker

The works range from as reductive as possible (Carl Andre’s work consisted of a piece of paper being stamped with a number from 1 to 1000, and thus the “image” was also the edition numbering of that impression) to opulent full-color imagery (Wesselmann’s required ten stamps). Some artists were deeply involved in paper choice (e.g. Sylvia Plimack Mangold), while others left the decision up to Parasol Press. More information for each piece is available on the exhibition’s webpage under each work.

This retrospective look at the Rubber Stamp Portfolio is the first time the entire suite and the existent archive of the whole project (correspondence, proofs, the rubber stamps used to make the works, etc.) has ever been exhibited. It is the second of a three-part series of exhibitions at Krakow Witkin Gallery that highlights and honors the efforts of Bob Feldman and Parasol Press. The series began with this past spring’s presentation of Agnes Martin’s 1973 project, “On a Clear Day” and will continue in the fall with an exhibition of Mel Bochner’s editioned works from the 1970s. In 2026, the Addison Gallery of American Art will mount a survey of Parasol Press’s entire history curated by Rachel Vogel. A section of this exhibition (focusing on the 1970s) will subsequently travel to the Print Center New York.

A few impressions of each artist’s contribution are available for sale. In addition, one complete suite of the thirteen prints is available to purchase.

Krakow Witkin Gallery would like to thank the family of Bob Feldman as well as Rachel Vogel and Carol LeWitt for their generous contributions of time, insight, enthusiasm, and support.

Giulio Paolini

Paths

June 21, 2025 - July 18, 2025

“Not this thing or this other thing, but a subject that can stand in for all possible subjects,

or, to the contrary, anything placed on the plane.”

–Giulio Paolini

Giulio Paolini (b. 1940, Genoa) engages the vocabulary of artmaking to explore limitless fields of possibility. The works presented in Krakow Witkin Gallery’s exhibition utilize image, language, and physical materials, all aspects of his practice that have evolved continually since 1960.

Paolini began making The Encyclopaedia Britannica (Fourteenth Edition, Vol. 12) in 1971 and continues it to the present. The works’ physical forms are that of lithographs identically reproducing a section of the entry for “infinity,” from the Encyclopaedia Britannica. The artist’s use of the encyclopedia’s entry (as opposed to giving a dictionary's simple definition, thus providing a more extensive meaning for the subject) points towards his interest in exploration as opposed to definitive understanding.

Paolini’s development of the work over the last four decades accentuates an intentional tension between permanence and change. The artist first signed an impression of the print in 1971 and dated it as such; since that time, he has periodically signed additional impressions and dated them accordingly. Each piece is numbered, beginning with impression number 1 in 1971, with that number being written with the format of an edition, but with Paolini considering the edition to be of infinity (each piece is numbered X/∞). As the works are partially made over time, while the image of the text never changes, they physically have lived different lives, a fact that is made visible through variations in printing and aging. With this practice, Paolini simultaneously remakes the work, makes new works, and continues an ongoing project and thus investigates the experience, idea, and understanding of infinity through a scenario where the seriality of printmaking exists in tension with the ever-changing nature of ideas and language.

Nove particolari in due tempi (Nine Details in Two Stages) (1984) is composed of nine unbound double-page spreads arranged along the perspective lines projected from a figure (reproduced from Abraham Bosse’s 1648 treatise on perspective) on the sheet placed to on the right-hand edge (not the center) of the composition. The perspectival lines originate, not from the right (writing/drawing) hand of the figure, which is sourced separately from Diderot’s 1763 “Encyclopédie,” but from its left where it is posed in the act of observing a scene using a string apparatus. As in the Britannica edition, this figure and its sources function as location- and time-stamped counterpoints to the larger work.

In the overall composition, Paolini balances between unifying and dispersing forces and repeatedly upends the hierarchy between artist, viewer, subject matter, source material and end-result. The engraved lines of the figure are contrasted by the rigidly clean and geometric rectangles on the eight other sheets of paper as well as by the straight but hand-drawn lines that unify the overall composition. In addition, the images of what can be read as clouds or the sea are also, visibly, grainy reproductions, multiple steps removed from their sources. Each of these fragmentary images is labeled with one letter of “Mnemosine,” the Italian spelling of Mnemosyne, goddess of memory and mother of the nine Muses. Paolini’s use of reference expands the meaning of the work and serves to acknowledge and focus on the idea of “reference” as a forever-shifting aspect of life. Order (perspective, recursive composition) and chaos (the seemingly haphazard placement of the sheets), the past and the present, the actual and the reproduced—these are all subjects within Nove particolari in due tempi (Nine Details in Two Stages).

In the photographic assemblage Solitaire (2004), Paolini constructs a quieter, introspective scenario of questioning. Encased at the center of a plexiglass box, a photograph shows the artist’s right hand holding a sheet of blank paper. The center of the print, including a section of the artist’s thumb, is cut away to form a rectangular aperture through which another, apparently blank, rectangular sheet protrudes. This sheet is in fact a reversed piece of another section of the photograph, which the missing central piece and several others are scattered at random, throughout the display box. In Paolini's own words: “The presence of the hand, the sheets that are still blank: this is the itinerary that reveals all that will make up the work, that is, its own path before reaching its fulfillment. The path of the hand without the work knowing.”

Giulio Paolini has had numerous exhibitions in art galleries and museums around the world. Among the largest are those that have been held at Palazzo della Pilotta in Parma (1976); Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam (1980); Nouveau Musée in Villeurbanne (1984); Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart (1986); Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome (1988); Neue Galerie am Landesmuseum Joanneum, Graz (1998); GAM Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Turin (1999); Fondazione Prada in Milan (2003); Kunstmuseum in Winterthur (2005); MACRO Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Roma (2013); Whitechapel Gallery, London (2014); and Castello di Rivoli -Museo d’Arte contemporanea (2020), Turin. Paolini has participated four times in Documenta in Kassel (1972, 1977, 1982, 1992) and ten times at the Venice Biennale (1970, 1976, 1978, 1980, 1984, 1986, 1993, 1995, 1997, 2013).

“The attention is analytical, but the result is enigmatic.”

–Giulio Paolini

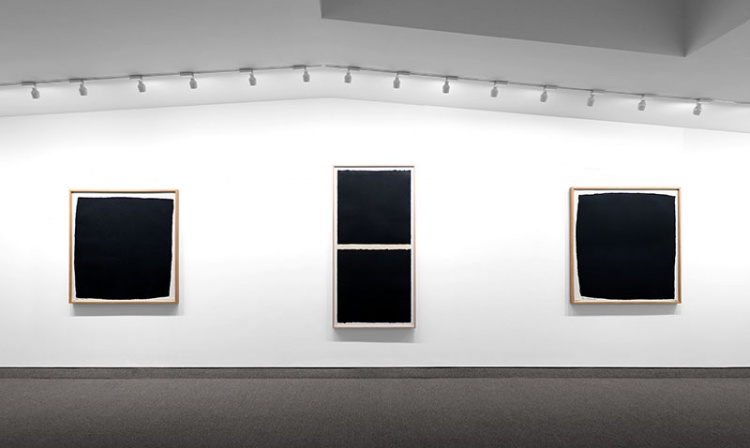

Allan McCollum

One Wall, One Work

April 26, 2025 - July 18, 2025

“What is it we want from art that our belief in ‘content’ works to hide from us?”

– Allan McCollum

Allan McCollum’s “Collection of Twenty Plaster Surrogates” is a collection of cast objects, each with texture and other aspects clearly showing that they were hand done. Each element has been painted to simulate a frame, a mat, and, where the picture would be, a black rectangle. They are clustered in the dense display style of a nineteenth-century salon. Each and every Surrogate is signed, dated, and notated. No two surrogates are identical; all those of the same dimensions have slightly different colored borders and “mat” shades. McCollum began the project in the mid-to-late 1970s.

Discussing the Plaster Surrogates in a 1985 interview, McCollum described his practice as, “In a sense, I’m doing just the minimum that is required of an artist and no more.”

To produce this work, McCollum and his assistants engaged in repetitive and communal labor. To a degree, he transformed the artist’s studio into a workshop and systematized the artistic process into stages of production: create molds, cast plaster, and the application of enamel paint to create a smooth surface. Although the panels were all executed in this way, no two panels share the same dimensions and frame color. McCollum asks viewers to rethink conventional distinctions between types of labor and to take into consideration the human effort embedded in all objects, artistic and otherwise.

“After mounting a few exhibitions I learned quickly that the Surrogates worked to their best effect when they came across as props—like stage props—which pointed to a much larger melodrama than could ever exist merely within the paintings themselves. The Surrogates, via their reduced attributes and their relentless sameness, started working to render the gallery into a quasi-theatrical space which seemed to ‘stand for’ a gallery; and by extension, this rendered me into a sort of caricature of an artist, and the viewers became performers and so forth. In trying to objectify the conventions of art production, I theatricalized the whole situation…”

McCollum, then, produces a surrogate of painting, an empty signifier that stands “in the place of social relations, objectifying them in a displaced way,” as George Baker has astutely put it. Trevor Starke writes, “The surrogate fulfills the task of painting: it facilitates aesthetic engagement and economic exchange, produces discourse, and takes up space on the wall. It does all the things that a painting should do. But it is not a painting. It is a fraud, a fake, a stand-in.”

Robert Bauer

Robert Bauer: Landscapes

March 1, 2025 - April 12, 2025

“Bauer's hand is intensely subdued, both distant and personal, inviting the willing viewer to be still.”

–Elaine Sexton

In 2014, Robert Bauer and Bronlyn Jones had a two-person exhibition with the gallery. Eleven years later, Krakow Witkin Gallery now presents a solo exhibition of Bauer's small landscapes in tempera and gouache, painted over the past five years.

“These are like conjured memories ... If they were only about depiction they'd be insufficient. It's their retraction from facts that makes them about the persistence of vision,” writes William Jaeger about Bauer’s work that was included in a 2017 exhibition at Skidmore College’s Schick Art Gallery.

Bauer paints with a keen attention to subtle detail through an exploration where he employs pencil notes, photographs, studies of other works sometimes of the same subject, and also more abstract memories of the time and place. Consistent with this layering is the artist's process of addition and subtraction. Bauer adds brushstrokes in a slow and steady process but just as carefully, he often sands and/or washes the painted surface so as to embed, subdue, and/or remove paint. The layering of sources and processes results in a balance of chance, choice, and control.

Poet and critic John Yau writes, “The reticence of Bauer's paintings mixed with his sensitivity to tonality and light suggests that he slows time down in order to register its passing.”

Robert Bauer was born in Iowa in 1942 and studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. He moved to Boston in 1985 and currently lives in midcoast Maine. Bauer’s work has been included in exhibitions at the National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC, the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art in Ridgefield, CT, the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York and Pratt Institute’s Manhattan Gallery. He is the recipient of three Massachusetts Cultural Council grants, two Pollock-Krasner Foundation grants in Painting, and he was a finalist in the 2006 Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery’s Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition. Bauer’s work is represented in public and private collections throughout the United States, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Harvard Art Museums.

“The atmosphere of hushed reverie”

–Elaine Sexton

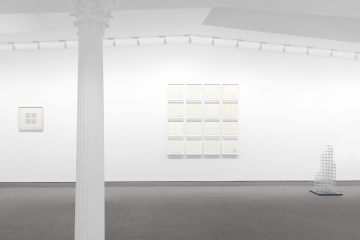

Agnes Martin

Agnes Martin: 1973

March 1, 2025 - April 12, 2025

"My ego is not satisfied to idle along with inspiration or put up a great fuss called “suffering.” It has to be subdued. The only way is isolation. In isolation there is no comparison no stimulation. Ego finally is quiet enough so that one can pay attention to other parts of the mind. Then drawing is possible."

–Agnes Martin

Agnes Martin created her only major print project, “On a Clear Day,” towards the end of a seven-year period (1967-1974) during which she made no paintings. Martin had moved to an isolated mesa in New Mexico to live in solitude. She had spent the previous decade in New York City, a time during which she had critical and commercial success but disliked the distractions of the city, desiring a quieter, clearer place to live where she could make her “egoless” art, imbued with beauty, openness, and joy. Invited to make a print project in 1971 by Robert Feldman of Parasol Press, it took her two years to bring it to fruition. The results were the 30 silkscreens of crisp lines and grids that make up “On a Clear Day.” Upon completion of the project, the Museum of Modern Art in New York held an exhibition of the project and was the first museum to acquire the entire suite.

In a 1973 review of the MoMA exhibition, Thomas Hess wrote, “[Agnes] Martin has become the object of a cult and, as if to back off from her admirers, has done a series of silkscreen prints, currently shown at the Museum of Modern Art. In these, she has stripped her image of all hand-quivers and fluttering variations to emphasize the mechanics of its linear structure. The basic schema is a square grid. The number of vertical and horizontal lines is different, so each square is filled with either thin or wide rectangles. Thus one work has nineteen horizontal lines and nine vertical ones, yielding squat, wide, tile-like rectangles. Another has nine horizontal lines and 23 vertical ones, with narrow, upright tiles. Other combinations include: 8-10, 8-2, 12-9, 19-12, 9-23, 6-23. Counting the lines in a Martin composition suggests the chiming quality of her work... In Martin’s paintings on canvas, these developments were accomplished with a refinement of touch which led many of her admirers to applaud her manual dexterity and sensitivity. Now she chooses to direct us to the bare bones of her art and expose the imaginative leaps that underlie her craft.”

In her private writings, Martin affirms the balance of calculation and intuition in her compositions, stating, “My formats are square, but the grids never are absolutely square; they are rectangles … When I cover the square surface with rectangles, it lightens the weight of the square, destroys its power.”

35 years later, in 2008, Kevin Salatino, then Curator of Prints at Los Angeles County Museum of Art and now Chair & Curator of Prints & Drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago wrote, "Grander in conception than any of Martin’s paintings, “On a Clear Day” condenses through multiplication thirty ways of constructing a grid, of expressing happiness, beauty, freedom, and the impossibility of, though yearning for, perfection. Its individual parts, recalling the number of days in a month, imply the passage of time. Its title declares the long-sought-for clarity the artist had struggled to find in the barren New Mexican desert. One of the great works of graphic art of the late twentieth century, “On a Clear Day” announces with luminous clarity and conviction Martin’s return to aesthetic wholeness.”

“I was thinking about innocence, and then I saw it in my mind—that grid … So I painted it, and sure enough, it was innocent.”

–Agnes Martin

Victoria Burge

January 11, 2025 - February 15, 2025

In her first exhibition with Krakow Witkin Gallery, Victoria Burge explores and extends the historical relationship between the Modernist grid and handwritten notation. Using found imagery in 19th and early 20th century diagrams and charts sourced from research libraries, Burge makes works that both transform and honor pre-existing visual codes and their makers.

For works on paper such as Sterope or her Untitled slate objects, Burge begins with a coded textile pattern and lets the diagram serve as foundational inspiration, rather than as rule. She reimagines the weaving notations using typewriter keys or hand-drawn markings, transforming the patterns in such a way that would nullify them in their former context, rendering them indecipherable to a weaver (a line extended just a hair too far, a mismatched pair of symbols, or a point left idling in space). Within the mark making, imperfections such as an off-center circle or a not-quite-straight line hint at the human labor inherent in even the most formal of constructions.

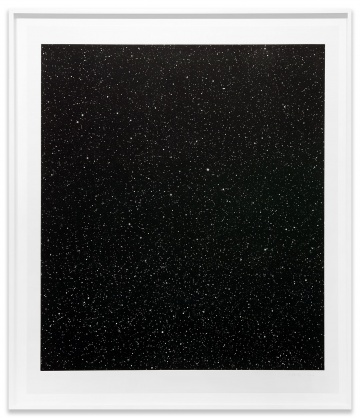

Sol LeWitt

Sol LeWitt: Early Drawings (1968-1975), Related Structures, and Prints

September 7, 2024 - October 5, 2024

Today, Sol LeWitt is equally known for his two- and three-dimensional works, but in the late 1940s, through about 1960, the artist focused on painting as well as drawing, and printmaking. By the mid-1960s, his paintings had transitioned through deeply impastoed paint, to paint on dimensional supports, to a focus on fully three-dimensional form. With this new-found focus, LeWitt began engaging skilled craftspeople to assist in the construction of his pieces (he called the works, “structures”). In order to communicate what he wanted, he drew fabrication diagrams using simple perspectival lines. Horizontal, vertical, and diagonal (in two directions) lines served LeWitt’s purpose of communication. Shortly after he started using this sort of diagram, he also began exploring drawing with these same four directions of lines (first on paper, then on walls) but now as the imagery with no external referents. With some time, he came to call this simplified imagery, “Lines in Four Directions.” The current exhibition focuses on early works made between 1968 and 1979 that speak to his exploration of “Lines in Four Directions” and that imagery’s relationship to concurrently-made three-dimensional works.

Throughout the exhibition, works are arranged so as to provide both context and counterpoint for each piece. Several examples are below:

A three-dimensional 1979 metal open cube structure has a grid of 3×3 cubes within it, so that it makes not just the 27 individual cubes but one larger overall cube, as well. Depending upon how one views the piece, one sees a dynamic arrangement of lines in four directions in space. Paired with this work, a 1971 etching consists of a dense field made entirely from lines in four directions. While the etching exists in two dimensions and the cube in three, the aesthetic and the exploration are deeply entwined.

A surprising work to be included in a solo exhibition of Sol LeWitt’s is an 1887 collotype by Eadweard Muybridge. Muybridge’s series of photographs, breaking down the stages of human motion from multiple equally-important vantage points, informs the grids of LeWitt’s works, which utilize Muybridge’s scientific method for LeWitt’s formally-reduced investigations. LeWitt gave this particular example of Muybridge’s work to a friend and colleague in a frame of his own making. Flanking this piece are two iconic works of LeWitt’s. A 1974 single open cube (defined by the 12 edges of a cube, rendered in metal that has been painted white) stands to the left of the Muybridge. To the right is a 1969 drawing, “Four Varieties of Line Direction.” Both works speak to LeWitt’s reductivist inclination. For the cube, while it initially appears simple, there are infinite ways to experience the defining border lines as well as what the cube “frames” through it. For the 1969 drawing, as described above, what once had been used merely as tools to describe something else, have become the focus of the exploration and now stand as an elegant drawing of quadrants of four different “sets” of parallel lines where the balance between the hand-drawn and the ordered, along with the contrast between the different directions of the lines, co-exist and provide quiet tension.

These juxtapositions are arranged in honor of LeWitt’s own methodology of presentation. “Straight Lines in Four Directions & All Their Possible Combinations,” a suite of etchings from 1973, exemplifies this gesture. Over fifteen sheets of paper, the artist presents lines in four directions and (and per the title of the work) all their combinations. The sixteenth sheet (the “colophon”) provides a diagram of the 15 in their proper arrangement and in the space of the 16th, places the text describing the project, so that when one hangs the work as illustrated on the 16th sheet, there is a set of nesting “images” where each smaller version is, in a way, equal to the larger one (the overall project is the same as the image of the 15 arranged on the 16th sheet, the text on the 16th sheet is equal to the entire project, etc.).

With all of these comparisons, differences, and relationships, it becomes clear that a key to an understanding of LeWitt’s work is his sense of equality. Three-dimensional and two-dimensional, open and closed, dense and sparse, big and small, imagery and text, idea and object, etc. were treated by LeWitt as equally significant. This exhibition presents the audience an opportunity to celebrate the eye and mind with which LeWitt approached life.

Fred Wilson

Fred Wilson: Master Plan(s)

September 7, 2024 - October 5, 2024

“I want people to see these works as I see them and I try to, without hitting people over the head, allow them to think … and either make sense of it or not.” (Fred Wilson)

Fred Wilson (b. 1954, Bronx, New York) has long investigated the meanings of symbols and objects as part of his multidisciplinary, research-based practice. Through alteration, juxtaposition, decontextualization, and selection, among other actions, the artist provides opportunities for new interpretations and associations that reframe social and historical narratives. Working across sculpture, painting, photography, collage, printmaking, and installation, Wilson imbues reclaimed images and objects with personal and historical importance. Legacies of colonialism and erasures of Blackness in Western European art are often the subject in his exchanges with these objects of different geographic and temporal origins.

For the current exhibition at Krakow Witkin Gallery, an early sculpture is juxtaposed with a rare, complete suite of photogravures to show both the depth and breadth of the artist's visual and intellectual explorations.

For "Art World" (1994), Wilson has taken a found globe and selectively removed Latin America, Eastern Europe, Africa, and most of Asia. Wilson has stated, "At this point I had sort of shifted it because it was really about that time and that the art world was only the United States and Europe, and all these other places were just not there." The art, though, is not just highlighting the absence, but what happens to the globe with that absence. The physical changes to the found object reveal to the viewer a thin structure supporting an incomplete, warped shape that one can see through but can no longer rotate smoothly. These are changes to the object that are both physical alterations and also serve as lenses with which to see the metaphorical ramifications of a limited "art world."

"THE MASTER PLAN or In Between the Big Bang and Modern Art is the Restroom" (2004-2009) consists of 22 photogravures where Wilson has employed specific gallery floorplans from visitor orientation maps of eighteen European and North American museums of anthropology, art, cultural or natural history. Omitted from these maps are all but a few words and icons of collection care terminology or visitor services signage. Displayed as an immersive installation of evocative but anonymous abstract forms, a viewer can explore one's own "master narrative" by comparing one plan or symbol usage to the next. The subtitle, "In Between the Big Bang and Modern Art is the Restroom" evokes an evolutionary perspective, the legacy of colonialism and imperialism, still embodied today in the organization of materials cared for by Western museums, supported in most cases by a hierarchically distributed space division. Hopefully, while the removal of information leaves room for assumptions, indicators highlighted by the artist enable a clearer path of thinking.

Wilson recalls that, at the beginning of his career, "working simultaneously in the educational department of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the American Museum of Natural History, and the American Craft Museum made me wonder about how the environment in which cultural production is placed affects the way the viewer feels about the artwork and the artist who made these things."

The artist’s early work was directed at marginalized histories, exploring how models of categorization, collecting, and display exemplify fraught ideologies and power relations inscribed into the fabric of institutions. His groundbreaking and historically significant exhibition "Mining the Museum" (1992) at the Maryland Historical Society, radically altered the landscape of museum exhibition narratives. As interventions, or “mining,” of the museum’s archive, Wilson re-presented its materials to make visible hidden structures built into the museum system, and American Society as a whole.

Commenting on his unorthodox artistic practice and how it has changed over time, Wilson has said that, although he studied art, he no longer has a strong desire to make things with his hands: “I get everything that satisfies my soul from bringing together objects that are in the world, manipulating them, working with spatial arrangements, and having things presented in the way I want to see them.”

His installations lead viewers to recognize that changes in context create changes in meaning. While appropriating curatorial methods and strategies, Wilson maintains his subjective view of the museum environment and the works he presents. He questions (and forces the viewer to question) how curators shape interpretations of historical truth, artistic value, and the language of display—and what kinds of biases our cultural institutions express.

One Wall, One Work: Sherrie Levine, Walker Evans, the Library of Congress, and others: The Burroughs Family (a collection)

September 7, 2024 - October 5, 2024

The current exhibition, “Sherrie Levine, Walker Evans, the Library of Congress, and others: The Burroughs Family (a collection)” took 88 years to come together. Below is a recounting of how and why it was assembled:

In June of 1936, Walker Evans traveled to Alabama with writer James Agee on an assignment for Fortune magazine to produce a new installment in a series of articles on the Depression and its effect on what the magazine considered “average” Americans and specifically for this assignment, sharecroppers. To do this, Evans took a leave from the Resettlement Administration (which was soon succeeded by the Farm Services Administration) where he was working, with the agreement that the negatives would become property of the US Government. While Fortune declined to print their article, Agee and Evans continued the project, ultimately publishing the book, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, in which Evans’s photographs prefaced Agee’s text.

In Alabama, over eight weeks, Agee and Evans had become familiar with three families of farmers in Hale County: the Fields, the Tingles, and the Burroughs. The writer and the photographer embedded themselves in the lives of these families, sharing their day-to-day experiences. Evans made photographs of the families, their homes, and their ways of life. In Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Agee notes that the Burroughs’ home, despite appearances, was only eight years old when the pictures were made. In addition to farmland and housing, Floyd Burroughs also leased farm equipment and, as payment, surrendered half his harvest to his landlord. He regularly ended the year in debt. Evans’ photographs neither romanticized nor criticized their subjects, they presented them.

In 1981, 45 years after Evans photographed these families, Sherrie Levine re-photographed reproductions of Evans’ work straight out of a book for a project she titled “After Walker Evans.” Evans was one of several male “artist hero” of classical Modernism that Levine had chosen to reproduce work by as a way of questioning traditional notions of the male artist as authority and/or genius. Levine’s use of the prefix “After” in her title acknowledged the chronological precedent of Evans while also referring to the widely accepted practice in the history of art of making copies “after” established masterpieces. By claiming these existing photographs as her own, as well as titling them as she did, Levine asked questions about authenticity, ownership, and originality, as well as how these aspects have traditionally been the basis for valuing works of art. Levine has stated, “The pictures I make are really ghosts of ghosts: their relationship to the original images is tertiary, i.e., three or four times removed."

The use of the word, “ghost” by Levine makes sense for her own work and it also resonates for Evans’ approach and the “lives” of the negatives from the Let Us Now Praise Famous Men series as, over the course of Evans’ life, the negatives had been used to make prints by Evans and by his associates, as well as by the Library of Congress itself (the Federal organization that manages the FSA holdings and owns the negatives). The definitions of the words “authentic,” “original,” and “vintage” are murky when it comes to these works.

Similarly, over the years, Levine had re-printed some of the images from “After Walker Evans” in various sizes (from approximately 3 x 5 inches to 9 x 13 inches). At larger sizes, one sees the quality of the reproduction being captured as much as the image of the Burroughs family, themselves. The 1981 prints were praised as a feminist hijacking of patriarchal authority and a critique of the commodification of art. Little comment has been made, specifically, about the various prints Levine has made since 1981.

With this sort of grey-zone being seemingly significant for Levine’s practice and also for the lives of Evans’ works, a presentation fully engaging the “ghosts” seems an appropriate way to present both artists’ works together. Central in the presentation is Evans’ own print, “Burroughs Family, Hale County, Alabama,” (the image of the entire family, standing against an exterior wall of the family home). Above that is Levine’s “After Walker Evans: 1,” (the image of most of Floyd Burroughs and his neighbor’s children standing against/near a porch post). Surrounding these two “original” photographs are other photos, all different images of the Burroughs, all from Evans’ negatives. The exhibition, as a whole, has vintage prints by Evans and by associates, and vintage prints by the anonymous printers at the Library of Congress. Also on exhibition are a number of 2024 digital prints that come directly from scans of the original negatives and were recently printed by the Library of Congress.

Furthermore, also included in the exhibition is the original 1941 book, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. It first came to publication with 30 images by Evans in 1941 and was met with little acclaim. It was reissued in 1960 (now with 61 images) and has since become a “classic” of American literature. Since that time, the book has been reprinted numerous times (with selective editing and re-sizing of the various images). Nine versions of the book are on display and available for perusing.

As a whole, the exhibition hopes to honor both Levine and Evans, as well as the numerous other people who have played significant rolls in these projects (Agee, the Burroughs, Library of Congress, and many others), and also attempts to bring forth the problematics of both artists’ practices so that they can be appreciated.

(The group of books and photographs are being kept together and sold as one collection.)

Michael Mazur

Michael Mazur: Paintings 1970-2008

June 15, 2024 - July 19, 2024

Join us for the public opening reception on Saturday, June 15th, 2024 from 3pm - 5pm

Julian Opie

April 20, 2024 - June 1, 2024

Join us for an opening reception with the artist on April 20, 2024, 3pm - 5pm

Back to all Member Galleries

Back to all Member Galleries